Melissa started the first grade at Luz-Carnide Elementary School in Lisbon this September. During the initial meeting with parents, the class teacher announced she would not continue teaching their class, Andreia Quintino, the mother, shared in a statement.

The teacher explained that after teaching hospitalized students for over 20 years, she felt unable to handle a class of 24 students and had requested a transfer back to the hospital. “We were alarmed considering the news about teacher shortages,” said Andreia Quintino.

Two weeks into the school year, “we received an email from the school notifying us that the teacher was on medical leave,” Andreia explained, noting that her six-year-old daughter only had time to learn “a few letters.”

The school administration attempted to hire a new teacher but was unsuccessful. While the vacancy is posted, there have been no suitable candidates. “The schedule remains open until a replacement for the class teacher is found,” stated the deputy director of Virgílio Ferreira School Group.

The shortage of first-grade teachers is a national issue, especially in the Lisbon area, the school administration noted.

A request for the current number of missing teachers was sent to the Ministry of Education, but there has been no response yet.

Meanwhile, the National Federation of Teachers reported that schools are searching for teachers for “133 first-grade classes,” affecting approximately “3,325 students,” according to their estimates.

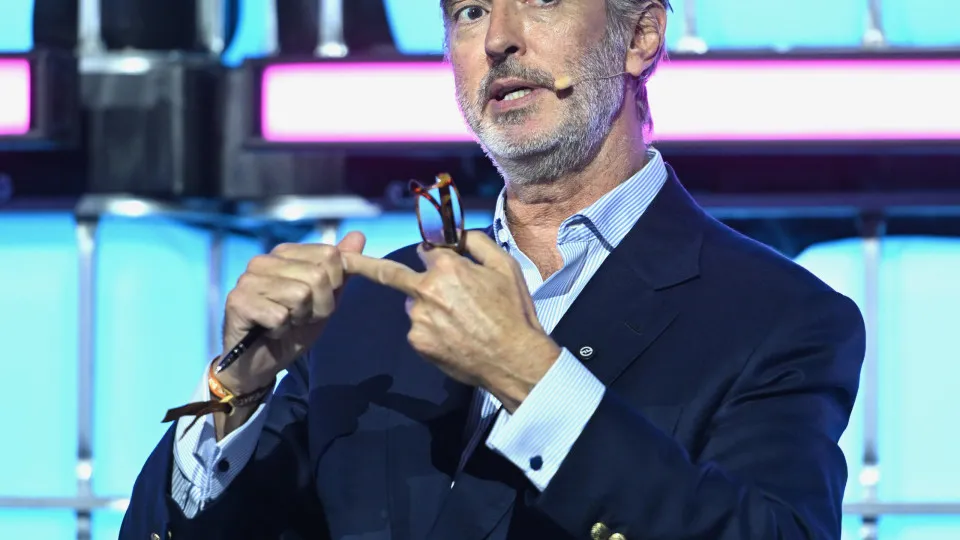

The Federation identified Lisbon as the most affected region, with the Virgílio Ferreira group being the second most impacted, following Almeida Garret group in Amadora, which has eight unfilled positions, said the Federation’s General Secretary, José Feliciano Costa.

The Virgílio Ferreira group reported that “since the start of the school year, four classes are without an appointed class teacher,” being managed by school coordinators.

Despite open vacancies, only two qualified teachers applied, one accepted, and the other declined.

At Melissa’s school, the interim solution was to utilize the school coordinator. However, “since the teacher coordinated the school and provided educational support, she only taught occasionally, and the students were then redistributed among other classrooms,” lamented the parents’ association president, Luís Garoupa.

Moreover, by the end of last month, the coordinator also filed for medical leave and stopped coming to school. Since then, students have been “distributed among different classes,” added Ana Rita Duarte, the group’s deputy director.

“It’s very challenging because teachers can’t give adequate attention to the kids,” warned Luís Garoupa.

Parents are concerned about their children’s learning. Melissa, who should be learning letters and diphthongs, spends her days in a fourth-grade class.

The school emailed parents asking them to help at home, “but it’s very challenging,” said Melissa’s mother, explaining that after a full day at school, children return tired and parents have “dinner and the next day to prepare: it’s one thing to supplement study; it’s another to teach.”

Parents requested the school utilize librarian teachers from the group or those providing support.

The school explained it has “no teacher solely supporting students who could take over a class. Using a librarian teacher is being considered should the Establishment Coordinator’s medical leave be extended.”

There is a librarian teacher in the group handling these substitutes, currently covering for an absent teacher, the administration explained.

Andreia Quintino expressed sadness that Melissa’s initial excitement for primary school has turned into anxiety about the unknown of the next day: “Often before sleeping, she asks me: ‘Will I be redistributed again tomorrow?'”

Parents appreciate the teachers’ efforts but claim the model isn’t viable for children without a teacher or for overcrowded classes. “These children are not receiving the same opportunities as others,” they shared.