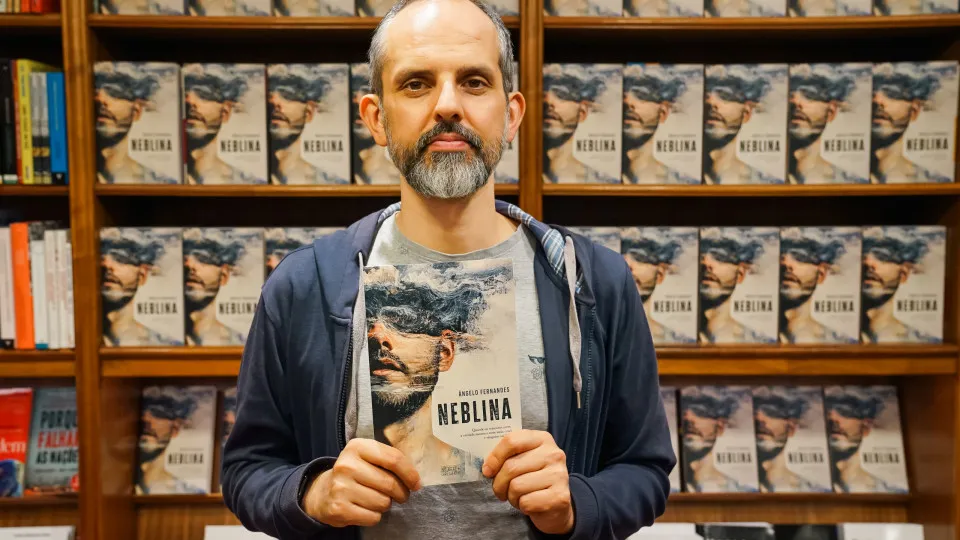

Intense and profound. This characterizes ‘Neblina’, the debut novel by Ângelo Fernandes, who won the National Prize for Playwriting in 2004 and founded ‘Quebrar o Silêncio’, Portugal’s first association supporting male survivors of sexual violence.

The book reflects over 20 years of writing experience and many years of working with victims of sexual abuse, among whom Ângelo counts himself.

Although it is a “fictional novel” and “not intended to be a technical book”, ‘Neblina’ displays Ângelo’s deep understanding of sexual violence and the family dynamics that perpetuate the silence and suffering experienced by victims.

However, the author avoids the graphic portrayal of trauma, steering clear of “stereotypical dramatizations”. He prefers the subtlety of “sensory memories, textures, and smells, instead of explicit images”. He was also “careful not to include certain terms or words” to prevent “arousing the morbid curiosity of potential readers”.

With a focus on the essentials, “emotions and feelings that survivors of sexual abuse experience,” and on “the internal journey and emotions experienced during the process of overcoming trauma,” the novel delivers a raw and often disturbing account, gripping from the first to the last page.

During an interview with Notícias ao Minuto, there was also an opportunity to talk about ‘Quebrar o Silêncio’, through which he has helped over 800 men and boys, combating the social stigma that still prevents many victims from seeking help.

You recently debuted in novel writing with ‘Neblina’, but the theme focuses on child sexual abuse, a crime you know well and have addressed for several years. Do you think this kind of literature can also help victims and their families?

I believe that literature can open spaces of reflection and empathy that often aren’t achieved by public or technical debates. When a novel embodies silence and pain, it allows readers to confront realities they might ignore. For some victims and families, it can be a point of identification, a recognition that their experience is neither alone nor forgotten. ‘Neblina’ is a work of fiction, not intended as a technical book or guide on child sexual violence, but if it can teach something, it is a very valuable complement.

What inspired you to write ‘Neblina’? Was there any particular episode? Is it inspired by someone?

‘Neblina’ does not stem from a single story but from a collection of experiences and observations gathered over years of working with male survivors of sexual violence. It is a fictional novel but with roots in reality. Every story is unique and should be treated as such, but there are commonalities with many other stories, which is where I center the narrative. My inspiration was to explore family dynamics, the silences that persist, and the lingering pains. That was the original focus; sexual abuse emerged as a theme to develop family encounters and clashes.

What symbolism does the title ‘Neblina’ hold?

The fog obscures, blurs vision, and makes it difficult to distinguish what lies ahead, sometimes for decades. It is also the environment enveloping the family in this novel, mirroring many Portuguese families. In the fog, nothing is clear; memories mix with facts, the truth does not reveal itself fully and can be partitioned into different perspectives. Only when the fog lifts does the weight of hidden trauma become apparent.

What challenges did you face writing a novel on such a painful subject?

The biggest challenge was balancing the need for truth with the responsibility not to exploit pain. I was always aware that ‘Neblina’ might disturb, but I never wanted to resort to stereotypical dramatizations or graphic descriptions. I believe this story required a different approach: referencing sensory memories, textures, and smells, instead of explicit images. During writing, I was careful not to include certain terms or words, keeping distance from anything that might arouse the morbid curiosity of potential readers.

The message I intend to convey is one of optimism: trauma causes deep marks, yes, but it does not have to define an entire life. It is possible to live free of trauma

What was more challenging: portraying the victims, the aggressors, or the environment where these crimes occur?

The most challenging was exploring the context in which everything happens: who is a victim, but also who observes or knows of the crimes. Is that observer another form of victim, or complicit in the crimes? I wanted to explore the silence present within this family, that sits at the table with them and occupies space without asking, aware of its discomfort.

What is the most important message you hope readers take away from ‘Neblina’?

Although it may be a hard read, those who have read it say it is intense, but also necessary and appreciated. I hope readers can peek into a breach of a universe still tied to wrong ideas, myths, and beliefs. The message I intend to convey is one of optimism: trauma causes deep marks, yes, but it does not have to define an entire life. It is possible to live free of trauma.

I focused essentially on the emotions and feelings that survivors of sexual abuse experience

How do your personal experiences and your work with ‘Quebrar o Silêncio’ intertwine with ‘Neblina’?

As I said before, sexual abuse was not the starting point, but a theme to explore family dynamics. Certainly, I did not ignore my story or those of so many men seeking help from ‘Quebrar o Silêncio’, but I did not focus on specific events. I focused essentially on the emotions and feelings that survivors of sexual abuse experience. The internal journey, the emotions accompanying us during the process of overcoming trauma.

Many men believe they cannot be victims, or that if they are, it questions their masculinity. Society reinforces this idea by doubting, ridiculing, or minimizing the accounts of male victims

Eight years ago, you founded ‘Quebrar o Silêncio’, a space supporting male victims of sexual violence. Can you specify how many men have sought the association during this time?

By January 2025, we recorded 830 requests for help from male victims of sexual violence. In 2024, we had 112 new support requests from men and 50 new requests from family and friends. These numbers are not just statistics, they reflect concrete lives, complex stories, and requests for help breaking a massive stigma.

Why did you decide to found this association?

I decided to found it because, in Portugal, there was no specific space to support male survivors of sexual violence. It always made sense to create a safe and specialized place where they could be listened to without judgment. It was a gap in our country that we decided to fill.

Do you feel there is still a stigma in society that means many men don’t seek help?

Yes, the stigma is enormous. Many men believe they cannot be victims, or that if they are, it questions their masculinity. Society reinforces this idea by doubting, ridiculing, or minimizing the accounts of male victims. Combating this involves speaking more on the topic, giving visibility to their stories, and ensuring support services are inclusive and specialized.

It is urgent to work for a society that promotes safety, allowing victims to break the silence and speak out about their stories without being scrutinized, attacked, or devalued

How does ‘Quebrar o Silêncio’ assist the victims who seek its help? And what work does it do in preventing sexual violence against children?

We support in various ways: through specialized psychological care, mutual help groups, and peer support. We also work on awareness, information, and training of professionals on sexual violence against men and invest in crime prevention, particularly against children.

What are the greatest challenges the association faces daily, and how can the association be supported?

Social stigma continues to reinforce the erroneous idea that men cannot be victims of sexual violence. We founded ‘Quebrar o Silêncio’ almost nine years ago and still repeat the same messages we conveyed in 2017. It is urgent to work for a society that promotes safety, allowing victims to break the silence and speak out about their stories without being scrutinized, attacked, or devalued.

Recently, you called on TVI to include a warning in a telenovela featuring actor António Capelo — accused, on social networks, by various students and others, of harassment and sexual abuse. How can this warning be made and how can it help victims of such crimes?

The request was simple: to include a warning before the episodes, informing the public that one of the actors was accused of harassment and sexual abuse. This does not replace justice, nor is it our intention, but it allows victims to know they are not alone and that the topic and allegations are not ignored. It is also a way of holding media accountable, showing that entertainment cannot be indifferent or override sexual violence.