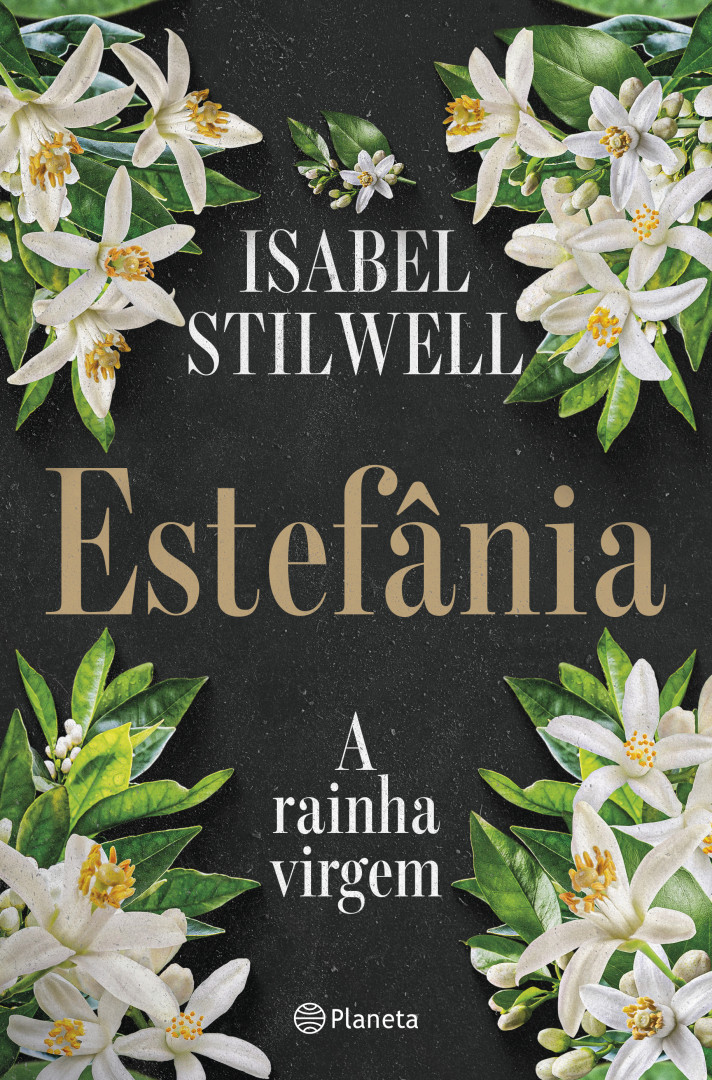

‘Estefânia – A Rainha Virgem’ is the latest historical novel by Isabel Stilwell. The journalist and author narrates the story of Estefânia of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, who married Pedro, the King of Portugal.

The tale explores the young monarch’s adaptation to the Portuguese court, her struggles in dealing with Pedro (despite falling hopelessly in love with him), and her distress over failing to fulfill her role as a woman and queen: becoming a mother.

We spoke with Isabel Stilwell, who provided details about the novel and highlighted one of the most curious aspects of this queen: the fact that, it seems, she died a virgin.

How are readers reacting to ‘Estefânia’, your new book?

The reactions have been very positive! Of course, we are still in the early stages, and people are saving the book for their holidays, but the feedback I have received is very enthusiastic. It’s a moving story that touches people. It’s about the love between Pedro and Estefânia, but the story is more complicated than that…

It’s a tragic story, as both die very young and leave no descendants…

In Queen Victoria’s letters to her daughter, she says it’s really awful, and not even a child remains from Estefânia.

I think we can already address the elephant in the room… Did Estefânia indeed die a virgin?

The knowledge [that the queen died a virgin] has been known since Ricardo Jorge’s article*. When re-examining it, the question is: ‘Is this really true?’. Despite everything, there are the so-called complacent hymens, and the autopsy revealed the presence of a hymen, although alone, today, it would not be sufficient to declare that there had been no sexual relations…

*Dr. Ricardo Jorge published an article in ‘A Medicina Contemporânea’ – ‘A parteonoplastia: ensaio de medicina ética sobre a revirginization’ (1909). In the article, as Isabel notes in her book, he wrote: “Queen D. Estefânia, wife of D. Pedro V, died, as is known, of diphtheria: as the false membranes spread over the vulva, the doctors examined her and were surprised to find the hymen intact”.

If we imagine women so removed from their bodies, with those dresses, everything very modest, it would indeed be a shock to share the body with someone else on a nightWhat gives strength to this conclusion?

It’s putting two and two together because it is not the only indicator.

In the first letter Estefânia writes, she says: ‘this is very unpleasant’. If we imagine women so removed from their bodies with those dresses, everything very modest, it would indeed be a shock to share the body with someone else on a night. However, when we start studying the letters, we have all the indications that she was available because in reality what she wanted most was to have a child.

Moreover, in the end she writes again to her mother saying: ‘I know mother only wants to come at the big moment’, which would obviously be childbirth, ‘but that might take a long, long time. Please, come before’. Normally, one wouldn’t respond like this. They always say, ‘maybe soon, maybe next week’, but one realizes – at least my interpretation – that she was trying to tell her mother it wasn’t going well.

I spoke with sexologists, psychiatrists, and a pelvic physiotherapist to try to understand if what I was saying made senseDuring your book’s presentation, you mentioned talking to specialists on the subject.

Yes. I talked to sexologists, psychiatrists, and a pelvic physiotherapist to try to understand if what I was saying made sense. The conclusion is that yes, there is the complacent hymen, but a young woman after 14 months of sexual relations would have very little probability of remaining a virgin with an intact hymen.

D. Pedro V was always saying that energy couldn’t be spent on the physical parts to save for the intellectual part. As he was a workaholic, he sublimated his libido and projected it onto his work

What was really happening with D. Pedro V? At the peak of his youth, he didn’t engage with any woman? It’s hard to believe…

He was extremely puritanical before [the marriage]. His biographers already said he never commented on a woman’s beauty, on how she enchanted him. When he met Charlotte of Belgium, whom he was supposed to marry, there was not a word to say. About Vicky, Queen Victoria’s daughter, he talks with friendship, but there is no physical comment, not even a cheeky one and yes of attraction.

Estefânia says she was the only woman he would talk to. She said Pedro would only choose the men in a room, talk only to them with intense conversations, he didn’t know how to make social talks and lost a lot because those who didn’t know him thought he was arrogant and unpleasant.

From the letters he wrote to Prince Albert, we understand that – and it was typical in this time – people possessed limited energy that was employed one way or another. He was always saying that energy couldn’t be spent on the physical parts to save for the intellectual part. As he was a workaholic, he sublimated his libido and projected it onto his work. He criticized his brother [Luís I] and father [Fernando II] a lot, saying they went out a lot at night, had women, and that weakened them. From childhood, he sublimated a lot.

And what is your perspective on this information?

When I started looking into all this, I realized that D. Pedro has a very strong relationship with his father until he is 16, at the time of his mother’s death, and then cuts off the relationship – and although he remains very dependent on him – he’s very angry with his father.

Estefânia, Prince Albert, and Queen Victoria were always saying they couldn’t all live in the same house as the father and siblings, because the court was made around the new king and queen, and while the old king was present, the court gave precedence to the old one.

He sulked, refused to speak during lunches and dinners, and refused to move house because his mother [Queen D. Maria II] said harmony in the family had to be maintained. He couldn’t break free of his father’s dependence but was always speaking ill of him.

I think D. Pedro V sublimated because he also ate very little, always had stomach problems. He denied the side that for him meant death: the pleasure of food and sexWhy was there such a break?

When Pedro wrote to Estefânia telling his own story, he described himself as a worker living for his mother – even in heaven – to recognize him. He admired her work ethic and bravery.

He was 12/13 years old when his mother began having those children born dead or died shortly after. [D. Maria II] Began to gain weight, though doctors told her not to eat, and was a woman doctors said ‘couldn’t become pregnant again’. She became pregnant again and had another stillborn and was at imminent risk of life. Then she became pregnant a third time and died.

If we think a kid, a boy who has adoration and a strong bond with his mother, sees her getting pregnant repeatedly, I think he starts associating in his mind getting a woman pregnant with death and putting the blame on the father.

I think he sublimated because he also ate very little, always had stomach problems. He denied the side that for him meant death: the pleasure of food and sex.

When he wrote to Albert and Leopold about Estefânia, on two occasions he noted: ‘fortunately, Estefânia knows how to sublimate the material aspects of marriage to companionship, loyalty, friendship, etc.’ At heart, he was looking for a companion, a mother in a way, so much so that Estefânia’s last phrase is “take care of Pedro”.

If you look at all the recommendations – I cite a book on the history of impotence through history – that was exactly what was recommended in the 19th century… Strict diet, physical exercise, trying other hobbies besides workBut for Estefânia, it wasn’t easy.

She became tired. Through the letters, one can see that at first, she thought she could change him, as we all do when we meet someone we like. At a certain point, she says: ‘he could change and doesn’t.’

But then she had enormous faith. The last letter she writes is dramatic, saying: ‘mother, say you will pray with us and we will move forward’. She also writes: ‘Now I’m being very strict with Pedro, not letting him work more than X hours, trying to change his diet’.

If you look at all the recommendations – in the bibliography, I cite a book on the history of impotence through history – that was exactly what was recommended in the 19th century… Strict diet, physical exercise, trying other hobbies besides work…

So there could be a clinical problem with Pedro himself…

I think there was sublimation, a blockage.

At the time, it must have been a huge taboo to talk about this openly.

A total taboo! Something that could not be put in any letter, not even an insinuation close to it, what it would be! The only person we see her getting close to is D. Pedro IV’s wife, Pedro’s grandmother. I found letters where Estefânia’s grandmother asks the empress to have a serious talk with her granddaughter.

And they probably sensed this for some time because before D. Pedro V married, the empress of Brazil, actually Duchess of Bragança, wrote to Estefânia’s sister and grandmother, the Queen of Sweden, saying the woman who came for Pedro should be experienced and go to a more open court. It was like saying: don’t send me a ‘green’ one because my grandson – although an extraordinary person – is melancholic, has low “energy”, is very still, and spends a lot of time sitting working.

In essence, they were two young people of 20 with their first love… Maybe, had it continued, one of two things: either she would despair, or he might change a little over time.

When you conduct research, how do you find the balance between fiction and fact? You must feel that responsibility.

People know it’s a historical novel, but I have my intrinsic journalistic rigor, which makes me feel I cannot go beyond that.

In this case, there’s a lot of information. Many of her letters since childhood, letters to her mother, Peter’s own diaries, biographies, Queen Victoria’s letters… Although the dialogues must always be fictional, I try to base them on the letters. But for me, Leopold’s notebook was very liberating. In the dramatis personae, I indicate to the reader: the letters all in italics are true, transcribed as they are.

Leopold’s notebook contains her thoughts, based on what I studied in the letters, based on what is universal for women to feel. In essence, to build this thesis, which is mine, of the reason that leads Pedro to fear consummating the marriage. It’s a very intense and solitary job, but I like it that way.

I began to dream again after handing in the manuscripts, and didn’t dream of things related to itAre there times when you feel ‘I’m fed up with this, I just want to finish’?

Oh yes! Those moments when I go window shopping or pick my granddaughters up from school because at a certain point I can’t take it anymore.

Then, as we get to know the story, we start saying ‘but everyone knows this’ and someone has to tell us ‘no, nobody knows, you know because you’ve been doing this for a year’.

There are moments of discouragement and intensity. I began to dream again after handing in the manuscripts, and didn’t dream of things related to it. Shortly after submitting, I dreamt of my late brother-in-law, as if there was a space allowing my brain to think of other things.

During this time, did you understand a bit of what Pedro V went through?

Exactly! If someone told me to go out for lunch, I’d say no because I had to work. It’s just like that [laughs].

Now that you’ve released the book, how do you live this phase? Do you rest or already start thinking about the next one?

I’m now in the phase of meeting readers, but I’m starting to have some openings and thinking ‘hmm, who will be next?’ But very hesitantly, I’m still in aftershock.

We spoke with Luísa Sobral about her debut fiction novel: ‘Nem Todas as Árvores Morrem de Pé’.

Mariline Direito Rodrigues | 07:07 – 21/03/2025