As democracies around the world face challenges from polarization, misinformation, populism, and a declining trust in institutions, it has become imperative to discuss the future of the system. The rise of the radical right poses potential risks for countries like Portugal.

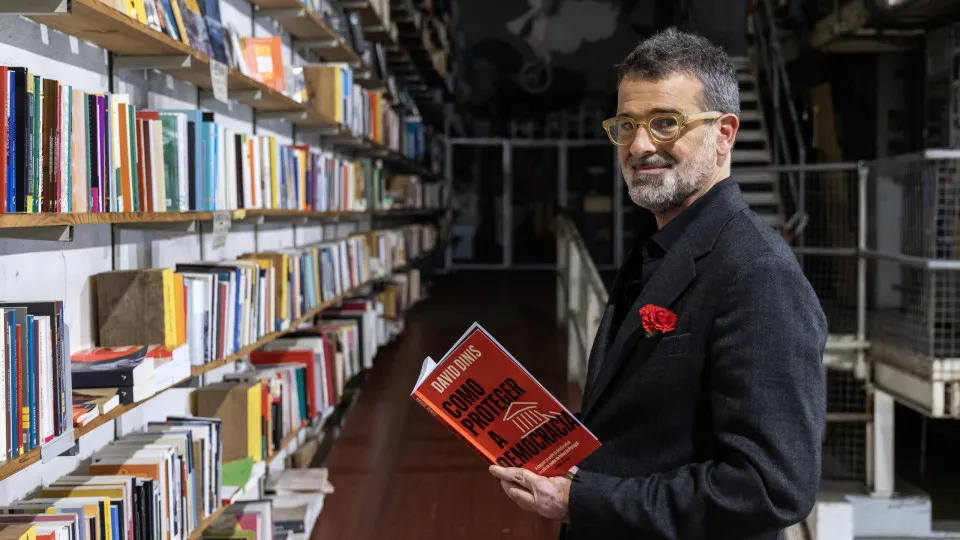

Journalist David Dinis, known for his long career in media as the deputy editor-in-chief of the weekly newspaper Expresso and a commentator at SIC Notícias, has contributed to this discourse with the launch of his book. This book, imagines a future where the party Chega, spearheaded by leader André Ventura, gains power.

“How to Protect Democracy,” released by Ideias de Ler, encourages readers to consider the potential repercussions of such a scenario. It highlights that “Chega is not like the other parties” and challenges citizens and institutions to consider what actions are necessary to “secure the future of Portugal” and uphold democracy.

In an interview with Notícias ao Minuto, Dinis shares his insights.

You recently published the book “How to Protect Democracy,” which anticipates the rise of the radical right. Do you think this scenario is inevitable?

I don’t think it’s inevitable, nor does it have to happen in the next elections. I looked into different surveys, opinion polls from various companies, and post-election studies which provide detailed data on the evolution of Chega’s electorate. My conclusion, based on this data, is that not only could it happen, but it’s also increasingly beyond the control of other parties to prevent it. An unexpected event, like an international crisis, could easily lead to Chega’s rise to power. I wrote about this before the latest polls, most of which confirm that Chega is practically on par with the Social Democratic Party and the Socialist Party, indicating a more substantial growth in Chega’s voter base than previously predicted.

We’re talking about suit-and-tie dictators. These aren’t the military dictators that use force. Still, we must acknowledge that these are democratically elected political parties.

What factors have contributed to the growth of the radical right in Portugal? This phenomenon is occurring elsewhere, but does Portugal, with its recent dictatorship history, overlook the past or desire a rebirth of Salazar?

There are several layers to this issue. Firstly, it’s crucial to note that we’re not dealing with a dictatorship akin to those prevalent in the 20th century. This is a path toward autocracy, or in simpler terms, a form of dictatorship, but it’s achieved without military coups or aggressive force seen in past dictatorships. Some books discuss this. We’re talking about suit-and-tie dictators. Still, these are elected political parties. Additionally, our dictatorship ended 52 years ago, and most of the current voting populace never lived through it, which partly explains why the dangers perceived 20-30 years ago are less evident today.

Furthermore, these political leaders began by adhering to democratic rules. Until now, Chega hasn’t broken any rules. The implication in the book is that once in power, they might easily violate them. I compare Chega’s proposals and speeches by André Ventura to similar-pattern parties, such as those in the United States, Poland, Hungary, and, to a certain extent, Italy with Giorgia Meloni. With this analysis, it’s clear numerous factors fuel populism’s rise in Portugal and others might support a party like Chega for varying reasons. These parties are adaptable, responding to current contexts with a versatile menu of ideas and actions that appeal to diverse electorates.

Having worked in several media outlets and currently being deputy director of one of Portugal’s prominent newspapers, Expresso, what role does media play in this development? Are the consequences considered, like giving radical party leaders frequent TV exposure?

Initially, the responsibility was decentralized. Chega attracted attention, initially due to curiosity, but there was a lack of foresight into how quickly they could grow. Chega’s news garnered substantial readership, tempting non-subscription-based outlets. Public awareness has since increased, yet Chega’s growth makes them unavoidable in political discourse. It’s now harder to exclude them. We might consider regulating Chega’s airtime. However, incentives remain strong.

Today, this issue is more pronounced in television than print media, driven by audience ratings. Broadcasting André Ventura attracts viewers, crucial for financially struggling channels. Additionally, there’s an institutionalization argument for covering the party as it’s now the second-largest in Parliament. Furthermore, channels justify their programming as catering to Chega’s audience, not just supporters of other parties.

There are numerous arguments…

Yes, various arguments are cited, yet André Ventura remains inordinately represented in media, especially during elections. His screen time during electoral campaigns has been unmatched among political figures, which seems unfair, particularly to other party leaders.

What can we do to secure the country’s future and prepare for this potential scenario?

Firstly, initiate discussion about media practices and contemplate the implications of Chega gaining legitimate power. It’s common to hear on the streets or among friends and family that “others do nothing” or “it’s indifferent to elect Chega or other parties.” Such discussions avoid confronting the reality that Chega is unlike other parties. Electing André Ventura and Chega, while legitimate, won’t yield the same consequences as electing any other parliamentary party, including the Liberal Initiative, Left Bloc, or Communist Party.

Why?

Due to Chega’s rhetoric and proposals. They regularly discuss systemic rupture and provide examples. The pattern among similar parties abroad suggests they won’t uphold democratic processes, instigating fear among non-supporters. In conventional democracies, election outcomes are accepted, with expectations that respective governments ensure respect for rights until the next election. There’s a genuine risk of this not holding true if Chega is elected.

In democracy, everyone plays a small role in its preservation. It’s not just a right but also our duty. Democracies don’t self-preserve; they require our care.

You depict in your book how democratic norms might be subverted. The scenario can induce anxiety. Is it not ironic that democratic votes could empower those intending to abuse it? Do Chega voters realize what might ensue?

I’m afraid not. There’s not a full awareness of what follows, which prompted me to write this book. Informed decision-making requires understanding the potential aftermath. We must gauge impacts, not just for dissenters but also supporters. Only then can we act preventively, engage in dialogue, understanding, and education. We all play a role in democracy’s upkeep. It’s both a right and duty, as democracies don’t self-sustain; they depend on us. This book is my small contribution to this collective mission.

What are the main dangers of a radical right government? Could we transform into an autocracy?

We see this conclusion in today’s United States, reflecting the outcome of eight years of populist rule in Poland and nearly 12 under Hungary’s Viktor Orbán. It’s crucial to note this isn’t mere theory. I depict a set of circumstances where individuals may feel the election consequences directly. Even André Ventura supporters aren’t isolated; they live alongside family, friends, and colleagues. Imagine a supporter’s friend or family member opposes Ventura’s government, or one is targeted due to minority status, or faced past court cases involving Chega members. These dynamics amplify risks.

A communist may feel threatened if street names honoring Álvaro Cunhal are removed, infringing on political freedom. An attorney defending a state-accused under Ventura might fear professional repercussions. Everyday protests might decline due to identification and retaliation risks. This isn’t solely about André Ventura. It mirrors conditions in the US, Hungary, and Poland, necessitating serious consideration.

Finally, do you believe there is still time to protect our democracy?

Yes, there’s still time because this hasn’t happened yet. It’s a fictional scenario in the book, allowing room for action. We can still discuss this matter openly. Parliament can adapt rules, laws, and the Constitution to mitigate future impacts. Until the scenario materializes, there’s time for dialogue. Post-scenario, the focus shifts to individual protection and efforts to restore normalcy.