“The recognition and enhancement of the career of forest rangers are needed,” stated Luís Damas, highlighting the work’s demanding nature and the significant effort and risk involved during summer. He also expressed a desire for increased funding for associations and forest producers’ organizations to better compensate teams.

During an interview, the president of the National Federation of Forest Owners’ Associations (FNAPF), which comprises 41 organizations across northern, central, and southern Portugal, argued that elevating the career’s profile would help retain top professionals.

While statistics on rural fires often emphasize the most damaging incidents, Damas underscored the crucial role of forest rangers in preventing significant blazes. “The first interventions by these teams are numerous, fending off fires that might have cost the state millions,” he noted.

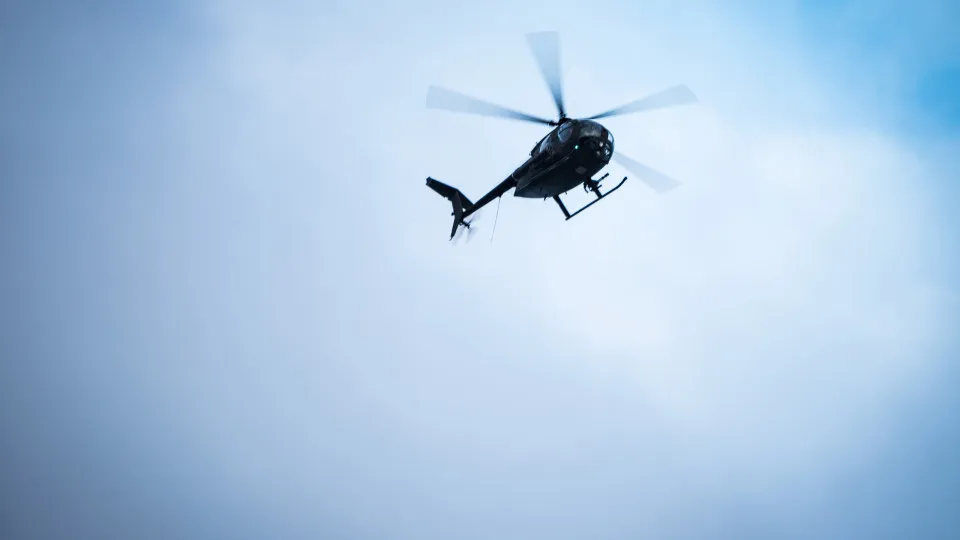

Damas emphasized, “Every intervention where a ranger team prevents a major fire saves on combat resources, such as helicopters and planes, and preserves the forest.” He also referenced the FNAPF, which operates seven ranger teams.

As a leader of the Association of Farmers of Abrantes, Constância, Sardoal, and Mação, he explained that the work rangers do is essential, yet not always visible during the summer. “They work year-round in forests and later support in mop-up operations,” Damas added.

“They are strategically stationed according to municipal forest defense plans and are not based in fire stations. Their familiarity with the areas they have worked in over the winter allows for rapid response to ignition points, unlike other units that may come from urban areas far away,” Damas highlighted.

Knowledge of the territory is considered “a significant advantage” by Damas, who noted that rangers are “evaluated annually based on their achievements and performance in fire situations.”

The 2024 report from the Agency for Integrated Management of Rural Fires (AGIF), released in June, detailed mobile terrestrial surveillance from May 6 to November 5. It involved “50,312 GNR patrols, 2,046 from the Armed Forces, 225 from the National Maritime Authority, 905 from PSP, 61 firefighters, 34,494 forest rangers, 2,325 Municipal Forest Interventions Teams (EMIF), 1,123 nature watchers, and 4,274 from other forces.”

In the secondary fuel management network, the forest rangers’ program executed 1,262 hectares, in service to the Institute for the Conservation of Nature and Forests (ICNF), with an additional 4,912 hectares covered in regular service, totaling 6,174 hectares.

Rangers must “work for the ICNF approximately 110 days a year, with 60 days allocated for prevention, and the remainder for public service,” in containment zones, “in the forest, not near houses,” Damas explained.

“In recent days, near Torre in Serra da Estrela, it was the rangers who worked hard on foot, as fire trucks couldn’t reach the area. Footwork with ranger equipment was crucial,” Damas remarked.

Since the program’s inception in 1999, audits by external entities occurred in 2010, 2015, and 2022. Annually, ranger teams must submit activity plans to the ICNF, alongside semi-annual and quarterly reports from July to September on surveillance work.

“There are semi-annual and quarterly controls, followed by an annual final report,” Damas explained, adding that some organizations sometimes face funding reductions due to incomplete reports or unmet area targets, emphasizing that “the ranger program is among the most controlled and audited programs around.”

The ForestWise evaluation report on the forest ranger program (PSF) from 2011-2021 identified eight main challenges, primarily revolving around “increased financial support” for teams, affecting all other challenges.

These challenges include the recruitment, professionalization, and qualification of rangers, access to suitable equipment, performance enhancement, improved cooperation between entities, team sustainability, and greater recognition and appreciation of the PSF.