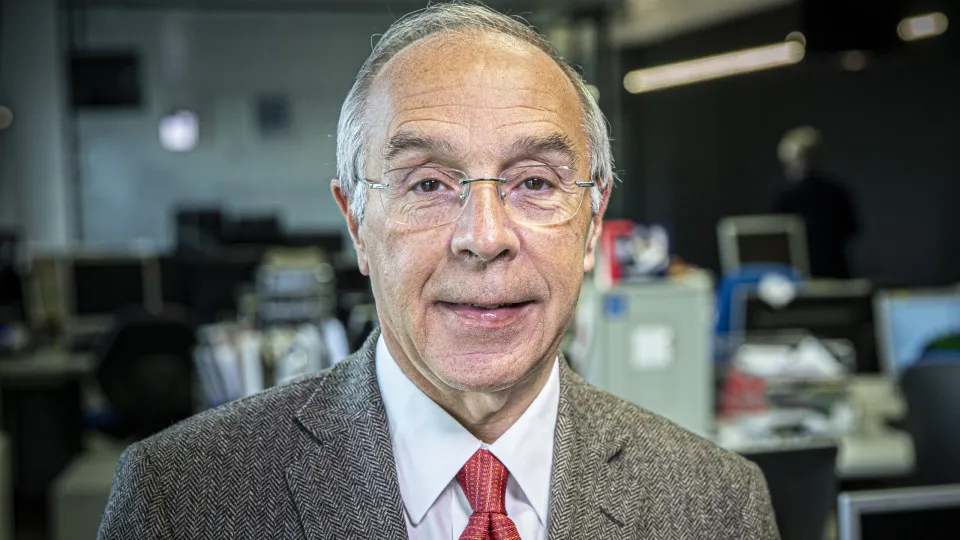

César Sá Esteves, a partner at SRS Legal specializing in labor law and social security, considers the “most controversial” change in the labor reform draft presented by the government to be the opposition to reinstating a wrongfully dismissed worker. The proposal allows employers to request the court to “exclude reinstatement based on facts and circumstances that make the worker’s return significantly harmful and disruptive to the company’s operations,” according to the draft legislation.

While current law allows for non-reinstatement in the case of micro-enterprises (up to nine workers) or when the worker held a management position, extending the measure to all companies regardless of size raises constitutional concerns.

“If there is an unfair dismissal, the natural consequence should be to ‘erase’ the illegal act and allow the worker’s reinstatement in the company that dismissed them without just cause,” explains César Sá Esteves, noting that the Constitution prohibits dismissal without proven cause.

However, the lawyer notes that when a court rules a dismissal illegal, “the worker most times opts for compensation plus the wages owed, rather than returning to the company.”

“This is probably the most sensitive change from a constitutional standpoint,” he added.

The jurist emphasizes that “many changes in this labor reform, whether one agrees with them or not, revert to measures that were previously in effect,” citing examples like the re-establishment of individual time banks, the end of restrictions on outsourcing after dismissals, and the extension of fixed-term contract durations.

For Madalena Januário, a partner at law firm RBMS and expert in labor and civil law, the two new measures that raise the most constitutional doubts concern changes to strike laws, with the proposed extension of minimum services to nursing homes, nurseries, food supply, and private security of essential goods or equipment, alongside revisions to collective labor agreements (CCT).

“Extending minimum services to sectors where they are not essential is limiting the right to strike as enshrined in the Constitution,” says the jurist.

Regarding collective bargaining revision, the jurist believes the changes undermine “the possibility of negotiation and inhibit arbitration,” both in assessing the grounds for termination and in suspending the extension period of agreements.

The reduction in deadlines, along with redefining criteria for applying and extending agreements, indicates a profound reshaping of the collective bargaining framework, which, according to legal experts and union leaders, could lead to increased labor disputes.

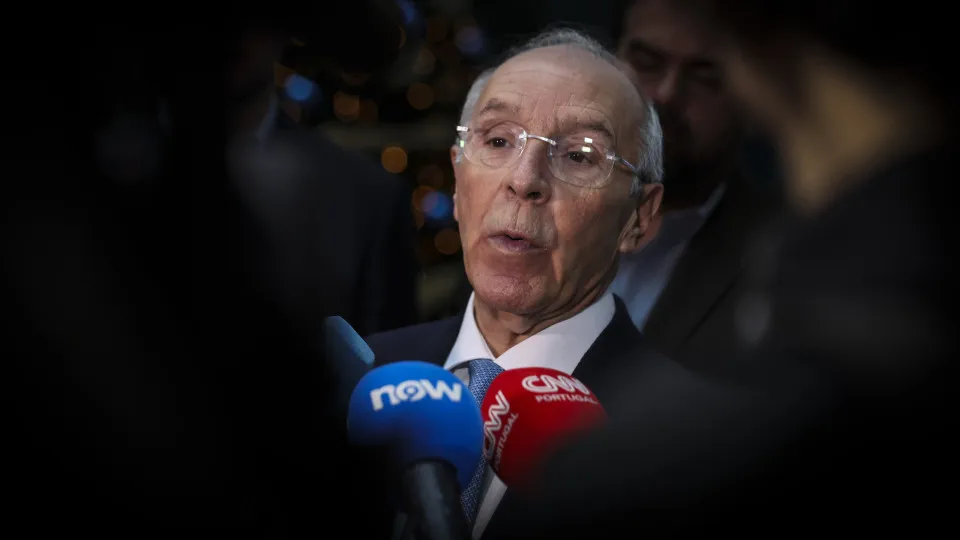

Diogo Orvalho, a contracted partner at Abreu Advogados, specializing in labor, social security, and pensions, acknowledged doubts about the constitutionality of measures like simplifying dismissals for just cause in micro and small enterprises and extending mandatory minimum services during strikes.

The lawyer noted that a procedure similar to waiving the presentation of evidence required by the worker, which the government aims to introduce into labor code to simplify dismissals for just cause, was already examined by the Constitutional Court in 2009. The judges found it violated the principle of adversarial process and the worker’s defense rights, ruling the provision unconstitutional.

This prompted the government, in amendments to the labor reform draft presented to UGT following the general strike announcement, to expand the restriction to small businesses (up to 49 workers), previously applied only to micro-enterprises (up to nine workers).

“With the government’s backtrack, I see a higher likelihood of the change passing the Constitutional Court’s scrutiny. Otherwise, it would hardly succeed.”

The extension of minimum services to new activity sectors, beyond those deemed “strictly essential” is, for Diogo Orvalho, “the most complicated issue” regarding constitutional compliance. “It may represent a partial limitation and a depletion of workers’ right to strike,” he believes.

The general strike against the government’s draft labor legislation reform will be the first joint action involving both major unions, CGTP and UGT, since June 2013, when Portugal was under ‘troika’ intervention.