The National Museum of Music, previously located at the Alto dos Moinhos metro station in Lisbon for nearly three decades, has relocated to the palatial area of the Royal Building of Mafra, previously used by the School of Arms during the 20th century.

“For many decades, the space was unused because it had no purpose, so we were delighted to move here. It’s also a way to rehabilitate a world heritage site that deserves attention, a new future, a musical future,” said museum director Edward Ayres d’Abreu during a guided backstage tour of the new setup.

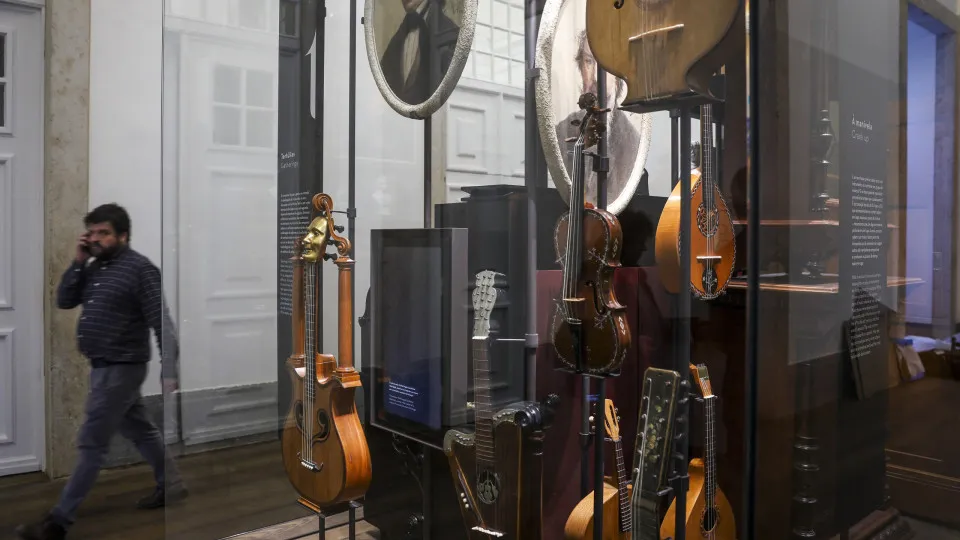

The entrance leads through a cold, austere corridor, featuring high vaults and the scent of paint and wood, into the museum space. This space comprises 15 exhibition rooms spread over 2,000 square meters, where large glass vitrines display hundreds of objects arranged to form a “living collection.”

“We will have around 500 objects on display, not just musical instruments, but also instrument-making tools, various paintings, iconography, scores, and phonograms, offering visitors a journey through music across centuries and regions,” added the director.

The museum also includes a larger area, approximately 7,000 square meters, which will house reserves and provide common spaces such as a café and a shop.

Unlike its previous incarnation, this exhibition is organized not around the technological aspects of the instruments but rather the contexts in which these instruments were used.

The musicologist explained that collectors often classify instruments based on their sound. However, here the focus is on “which musicians played which instruments, when, and in what context,” rather than technological aspects.

“We talk about concepts like the transcendental, power, how music can represent a state, and how it can be a means to explore the known and unknown,” stated Edward Ayres d’Abreu, describing an experience that invites a reconsideration of music’s place in everyday life.

Visitors will notice the curatorial effort to dialogue contrasting instruments, such as classic pieces adjacent to a self-portrait by former rapper Allen Halloween, reco-reco samples next to Barcelos whistles, instruments from the 12th century beside those from the 21st century, and Portuguese instruments alongside Chinese, African, and other European instruments.

“Despite being contrasting and seemingly distant, these instruments have much in common—they were used in similar contexts and for similar purposes. It’s this rich dialogue between distant objects that we aim to highlight.”

The rejuvenated Music Museum features items lent by the National Tile Museum, the Soares dos Reis Museum, the Biscainhos Museum, the Museum of Mechanical Music, the Museum of Contemporary Art, and private collectors.

In the museum’s quiet but chaotic spaces, the contrast is evident between the organization of completed rooms with illuminated, vibrant displays and the disorder of stacked crates, scattered boxes, and tangled cables and plastics littering the floor.

One such room, named “Plurality of Listens,” is an immersive hall where visitors are “invited into a space surrounded by 22 sound columns and four giant LED screens. At the center are devices that translate sound into tactile vibrations, felt with hands and feet,” he elaborated.

In this multimedia space, which will also show documentaries, there was still significant activity with workers using various tools, balanced on scaffolds, or climbing ladders to hang large, heavy curtains along the walls for “essential acoustic control.”

“The vaults were treated to reduce reverberation, and now the curtains will help further,” explained the project leader.

This initiative is part of the museum’s new direction to create a multisensory and inclusive space. Besides being able to feel sound, another room will offer an olfactory experience. There will be a video guide in Portuguese sign language, audio descriptions for the blind, and vibrating vests to amplify and enhance the vibrations felt with hands and feet.

In keeping with this interactive approach, all rooms will feature at least one instrument that visitors can play; the first is a gong, with three different mallets producing various sounds.

“The instrument becomes part of the musician’s body. It’s intriguing for visitors to experience this—hold a tuba or a piccolo [available in one of the rooms], and try out the sound, the weight, or simply touch them.”

Two men passing through the room, carrying a large object wrapped in white paper, were approached by the museum director, who requested to see the “exact replica of a 17th-century harp, displayed in one of the vitrines.”

One of these men is Orlando Trindade, the cordophone maker who crafted the piece, and conducted several restoration projects. He created this instrument for visitors to play.

“I tried to make it as close as possible to the original, but with my touch. I had never made a harp before; it was my first time,” he shared, showing how to play it.

Among the displayed pieces, some received special attention from the museum director during the tour, such as a cello Stradivarius once owned by D. Luis, a Regal, described as “a jewel” from the 16th century, lent by the Lisbon Academy of Sciences with unknown origins, the oldest table pianoforte in the Iberian Peninsula, two tambourines painted by D. Carlos, and a harpsichord from Louis XVI.

The research conducted over the past two years since the museum closed in Lisbon, in preparation for the relocation project, has allowed the team to “better understand the collection” and uncover “significant facts such as misdated items and incorrect attributions, and even the total number of instruments was adjusted,” the director revealed.

“Through our restoration and conservation campaign, we discovered very significant pieces which we plan to classify as National Treasures. These objects are exceptionally rare, technologically advanced for their time, in excellent condition, and crucial for understanding what music history was and, to some extent, may become in Portugal,” highlighting close to half a dozen pieces.

One surprising discovery was a cacophone, “an extremely curious and sophisticated instrument not found anywhere else,” whose origin was understood only after careful investigation: an almost unknown amateur working in a pottery in Alcoutim.

Still under installation is a “room that will talk about the voice as an instrument,” featuring a megaphone, a lamiré, multimedia instruments, and even a Drilbu, used in Hindu religious practices to mark recitation.

Edward Ayres d’Abreu surveys the unfinished rooms, the hustle of people finishing installations, the boxes and materials scattered around, debris to be sorted and cleared, just days before the opening scheduled for Saturday, from which point entry will be free until the end of November.

Asked if he feels panicked about the remaining work, the museum director smiled and replied, “We’re always in a panic, but everything is under control.”