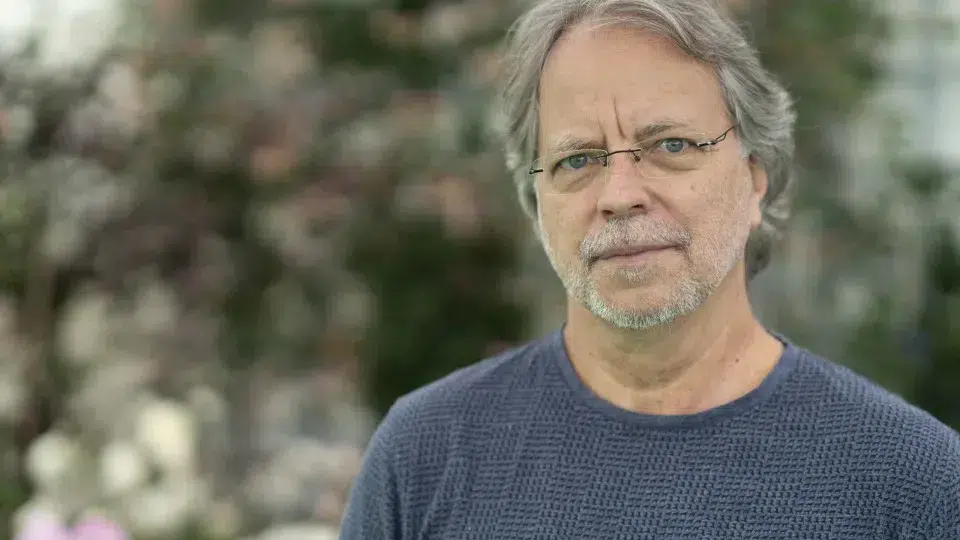

The book titled “25 de Novembro: O retrato de um país dividido” by journalist Paulo Moura (Objectiva – Penguin Random House) includes interviews with figures such as Chega’s deputy Diogo Pacheco de Amorim, former union leader Manuel Carvalho da Silva, and historians Jaime Nogueira Pinto and Irene Flunser Pimentel.

In statements to Lusa, Paulo Moura noted that, as the government plans the celebrations of the 50th anniversary of November 25, 1975, he wanted to reflect on the country’s past and present divisions.

At the time of November 25, “the country was deeply divided, to a point where we were on the brink of civil war. The civil war was imminent because the country — or at least there was this perception — was absolutely split into two,” he said.

Fifty years later, Paulo Moura believes that something similar is happening in Portuguese society: “The country is once again deeply divided, with an irreconcilable division between sides that cannot even dialogue with one another.”

“My reflection is about understanding whether these divisions have any relation to those that emerged back then,” the journalist stated, highlighting his interest in determining whether historical divisions within Portuguese society persist, such as between the North and South, urban and rural areas, or conservatives and progressives.

“Are the divisions we face today the same? Or is it a completely different issue stemming from cultural wars imported from the United States? To what extent does this new division fit into the old endemic Portuguese divisions? The book reflects on these issues,” he said.

Although he admits not reaching definitive conclusions, Paulo Moura emphasizes that everyone he interviewed, from left to right, agreed on one point: “Portugal today is a divided country.”

“Where this division comes from, whether it’s truly real or somewhat imagined, is unclear. But the truth is, we’ve never seen such heated, violent discussions, with people who are irreconcilably different in opinions. So, this division exists, it’s very strong, and it’s very concerning,” he remarked.

Comparing it to November 25, Paulo Moura notes that today’s divisions do not appear “as real” as those experienced in 1975, when the country was “on the brink of a civil war,” and seem more based on “cultural wars.”

However, the author pointed out that today, 50 years after November 25, ideas from the far-right, which he considers the principal loser of that day since all parties from that political area were outlawed, are beginning to resurface.

Paulo Moura believes it is within this context that the government’s commemorations of the 50th anniversary of November 25 are framed, which he estimates will serve as “a sort of right-wing revenge to reclaim these 50 years during which the left laughed.”

Nevertheless, the author asserts that November 25 cannot be equated to April 25, stressing that “what defined the new regime happened on April 25,” and the goal of November 25 was essentially to “restore the initial ideals” of the Carnation Revolution.

“While April 25 is a date that shines in the dark with its own light, November 25 does not, it only subsists illuminated by April 25,” he summarizes.