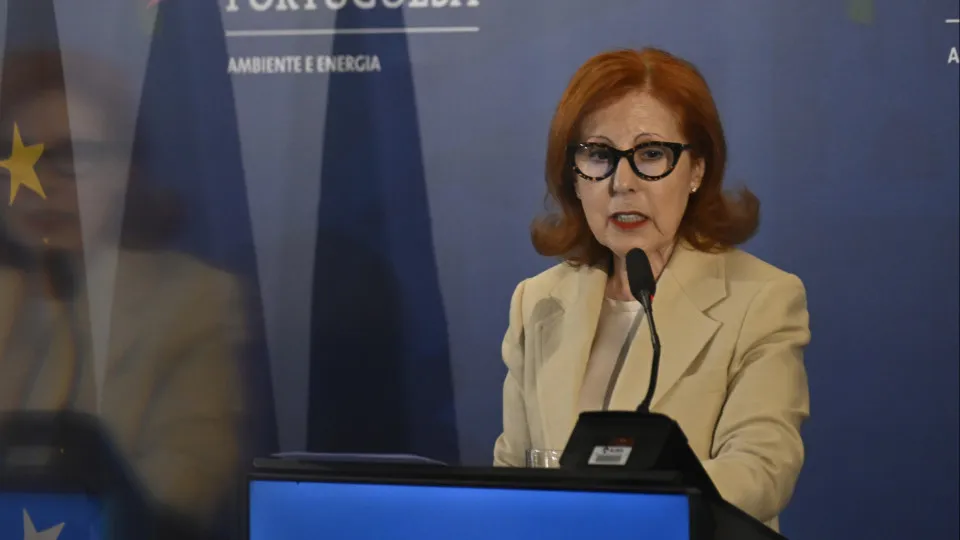

“There is significant pressure from oil-producing countries, which do not want to reduce emissions,” stated Maria da Graça Carvalho, during the deadlock in negotiations on the final day of the 30th United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP30) in Belém, Brazil.

Speaking to Portuguese journalists after an EU group meeting, Maria da Graça Carvalho explained that there are two groups with opposing interests.

On one side are the European Union, the United Kingdom, Latin America, and small island states, advocating for a clear roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels to be explicitly stated in the final document.

“On the other side are the 22 countries of the Arab group, with Saudi Arabia being very vocal, Russia—which I have not seen so vocal in a long time—India, and, to a lesser extent, China,” said Maria da Graça Carvalho.

These nations oppose not only the ‘roadmap,’ as the COP30 presidency calls the plan to end fossil fuels, but even the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, agreed upon in the Paris accord a decade ago, she noted.

In today’s meeting with delegation leaders to try to reach an agreement, these countries delivered “inflamed speeches” justifying the need to increase their emissions for development, recalling that the West developed its economy at the expense of the industrial revolution over 200 years.

Opponents of the fossil fuel phase-out argue they are not obligated to meet Paris targets as they fall under emerging and developing nations, but the minister reminded that in Paris, it was agreed all countries must comply.

The mitigation of climate change impacts, which includes requiring countries to submit periodically reviewed climate plans (known as NDCs), is another contentious negotiation topic.

The third point of contention is the demand, explicitly in today’s Brazilian presidency proposal, to triple financial aid from developed to emerging and developing countries, from $40 billion to $120 billion.

In this matter, Europe has insisted on not increasing the total funding established at COP29 in Baku, set at $1.3 trillion annually, with $300 billion provided by states.

Nevertheless, Maria da Graça Carvalho acknowledges potential flexibility to increase funds for climate adaptation within this total, as a bargaining chip for emerging and developing countries to concede on mitigation, potentially breaking the negotiation deadlock.

According to UN Conference rules, the final negotiation text must be the result of consensus among all participants, not merely the support of a majority of states.

Today, the European climate commissioner linked any potential increase in European funding for climate adaptation to greater ambition in mitigation.

“If we collectively decide on mitigation here, then you can ask the EU to step out of its comfort zone regarding adaptation funding. (…) And only if all mitigation elements I mentioned” are in the agreement, Wopke Hoekstra said during the negotiations of the document published today by the Brazilian presidency of the UN climate conference.

Hoekstra admitted that the UN climate conference might end “without agreement” as he deemed the Brazilian presidency’s COP30 proposal unacceptable.

The proposal, released early today, lacks any reference to the abandonment of fossil fuels, a requirement demanded by dozens of countries and the EU.