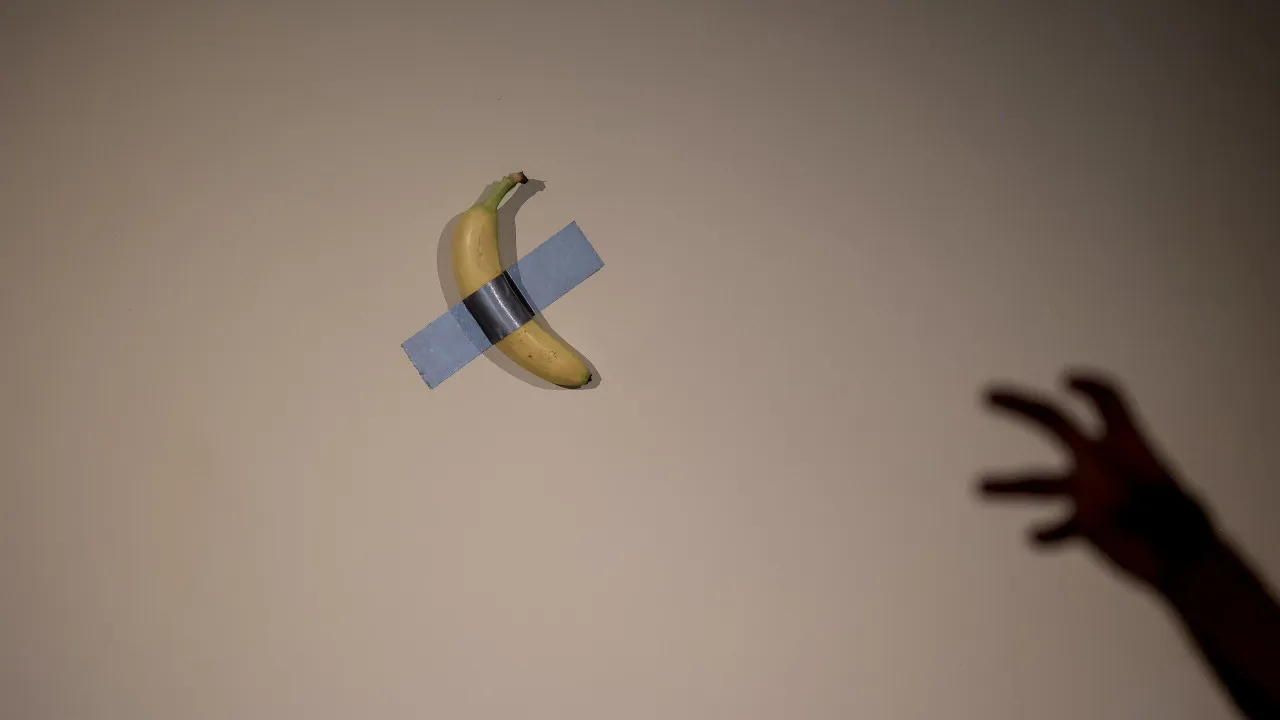

A free-entry exhibition, open until January next year, brings together several iconic creations by Cattelan—known for his controversial art, such as the banana duct-taped to a wall exhibited in 2019—presented in Portugal for the first time in a show specifically designed for Casa and Parque de Serralves.

“We selected a strict assortment of works that, to me, form the core of his output. This was the objective. He’s a court jester, not a clown, and he uniquely possesses the power to speak truth to power. This is a crucial aspect of his work and the art world in general,” remarked the museum director and exhibition curator, Philippe Vergne, to Lusa.

Vergne described Cattelan as a self-character, inspired by theater and the Italian tradition of ‘commedia dell’arte.’ However, the artist, a “jester” who “laughs when we cry and cries when we laugh,” was absent from the media visit.

Without the artist present, the curator, who had long intended to curate a collection of works by the Italian born in Padua in 1960, guided journalists through 26 works focusing mainly on themes of history, fascism, religion, an obsession with iconography, theater, death, and self-portrait.

A cluster of bananas on a worktable caught attention during the final adjustments of the Exhibition Service before the media tour commenced, led by Philippe Vergne, surrounded by covers, cleaning products, triple plugs, a water gallon, and duct tape.

The exhibition’s curator discussed Cattelan’s focus on fascism with the journalists, beginning with “Novecento” (1997), a horse suspended in the air, its body weighed down by history (evoking comparisons to Bertolucci’s film of the same name), before deciding where to direct the tour—settling on the room featuring “Untitled” (1997), an ostrich burying its head in the ground, a self-explanatory sight for today.

A fascination with religion permeates several pieces, from a 2018 small-scale Sistine Chapel redux that rebalances humanity’s relationship with the divine in a room too small for all present, to the renowned “La Nona Ora” (1999), featuring Pope John Paul II struck by a meteorite, one of the artist’s signature works.

“Jorge” is a homeless figure at the chapel’s entrance, with another piece engaging with the theme of religion, visible to passersby on the street, echoing scenes visible around Porto and other European cities.

Inside, a child bearing the face of Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler appears in “Him” (2001), kneeling in prayer at an altar swarmed by pigeons, one of several “ghosts” set throughout the full installation, inviting a “negative epiphany” about the dangers of reverting to darker times.

There is also an “elephant in the room,” “Not Afraid of Love” (2000), draped in a white shroud reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan, and a mechanic child’s drum gradually draws attention with its sound.

“I know you want me to talk about a banana, but there are no bananas in this exhibition,” Vergne joked, leading to the room where the most iconic of the Italian’s works is displayed under dim lighting.

Because “he’s a comedian,” like the work’s title, and not a banana, as a pipe is not in René Magritte’s famous painting, this room is dedicated to the ‘meme,’ the power of a 2019 creation that “is still being talked about today.”

In November 2024, one piece of “Comedian,” here with a banana bought at a local supermarket near Serralves, was auctioned in New York for 6.2 million dollars (5.9 million euros) to a cryptocurrency entrepreneur.

Since it was first shown in 2019 at an art fair, selling for around 120,000 dollars, “Comedian” has become a global event with a significant impact “on contemporary cultural consciousness,” stated auctioneers Sotheby’s in a release at the time.

The artist did not receive any proceeds from the auction sale, as the seller was a collector and not him, after initially paying 35 cents for the ‘original’ banana from Shah Alam, a vendor situated near the New York Sotheby’s.

“Nobody talks about the duct tape,” jokes Vergne, trying to discuss the much-discussed creation as little as possible, or with irony mostly, while highlighting other works, despite journalists’ persistent inquiries.

“Sunday,” from the previous year, occupies a wall with gold-plated steel panels studded with bullets and nine white-covered corpses, a recent work—”an ornament of despair, an ornament of violence,” engaging with Italian Arte Povera from the 1960s and 1970s, facing “All” (2007), nine white-covered corpses, referencing September 11, 2001.

“Daddy daddy” (2008), a Pinocchio ‘drowned’ in Serralves lakes, head downwards, proves, to the director, that “if you lie, you die, that’s how the game is played today,” and acts as a meta-synopsis of the exhibit—a character created by Cattelan, like Geppetto made the wooden boy, replicating strong themes of deceit, suicide, politics, personality, and theater that mark the rest of the show.

Apart from the ongoing exhibition until January, Serralves is also launching a publication dedicated to it, featuring a visual essay by the Italian artist and texts from Philippe Vergne, Bernard Blistène, and Cecília Alemani.

The exhibition’s curation—at the park also featuring an enormous middle finger displayed towards the park, having previously faced the Milan Stock Exchange—is by Vergne, coordinated by Giovana Gabriel with support from the Perrotin Gallery and the Gagosian Gallery.

Born in Padua in 1960, Maurizio Cattelan, a self-taught artist, gained fame for his provocative and satirical style in artistic creation, marked by hyper-realistic sculptures and installations, earning a reputation as a ‘prankster’ and recognition since the late 20th century, through a retrospective exhibition in 2011 at the Guggenheim in New York, and the viral case of “Comedian” in 2019.

“I remember walking in New York, I asked Cattelan what he was reading, and he replied, ‘A biography of Napoleon.’ I began to understand his relationship with history. I know how he is perceived and who he is in the art world. There’s a perception he created, which serves almost as a refuge, and [that of] people viewing his work,” states Philippe Vergne.