The buried body, the holy body, and the classified body are the focus of a journey mapped by the writer and independent researcher Rafaela Ferraz, whose work “Portugal de Morte a Sul” opens the door to reflection not only on mortality—our own and that of others—but also on how we treat and manage the dead.

With a degree in Criminology and a master’s in Legal Medicine from the University of Porto, the 33-year-old expressed in a conversation with Notícias ao Minuto that she has always had an “interest in everything that is on the margins” or “that we don’t like to talk about.” This curiosity was encouraged by her family, who took her to visit the Chapel of Bones in Évora when she was about five years old.

Born with it or not, the interest translated into a quest for the way we exhibit the dead body, taking us on a journey through Portuguese cemeteries, churches, and museums. As Rafaela Ferraz recalled, “the body of a saint is not exposed for the same reasons as an ancient Egyptian body in a museum.” Indeed, according to the researcher, “the way we treat our dead and the dead of others is very different.” The depersonalization of some ultimately proves “that death is clearly not the same for everyone.”

Funerals and wakes also give us a space where we don’t have to do anything but mourn. This is something we have been losing in our societies. We no longer have the practice, for example, of prolonged mourning, or wearing black to signal to people around us that we are in mourning and that something is happening to us. No; we lose someone, three days later we’re back at work, and it’s expected that life continues as it was before

How did you enter this almost literal sub-world of mortality? Was it something you were always curious about, or was it something nurtured by your parents?

A bit of everything, really. I’ve always been interested in things that are somewhat on the edges, those topics that are a bit more taboo, the things we don’t like to talk about. I’ve always been very interested in stepping off the beaten path, so to speak, and I was lucky to grow up in a family where those interests and all my other interests were encouraged. So, if I wanted to read about paranormal phenomena, I could; if I wanted to read about ghosts, I could. There wasn’t really anything out of bounds. The interest may have been innate, it may have been natural to me, but it was always very encouraged or at least not restricted by the people around me.

As for mortality, we arrived a little later. My academic background is in Criminology, then in Legal Medicine. In the master’s in Legal Medicine, I began to focus a bit more on funeral practices and the functioning of cemeteries in Portugal; how they work logistically, how we manage the dead… It’s an expression that sometimes shocks people, but it’s true—they have to be managed just like any other urban phenomenon. Then, all these questions about the body, what happens to the body, and why, in most cases, we make the body disappear. A person dies, we go to the wake, we go to the funeral, and we never see them again. In other situations, like those I describe in the book, the body is deliberately exposed for us to see. That’s more or less the journey, and we’ll see where we end up in the future.

It’s quite curious to have been encouraged to all these ‘adventures’ because society usually tries to hide death from children. When someone dies, it’s common to tell them they “went to meet Jesus” or “went to heaven”… It’s quite interesting that the opposite happened to you. Shouldn’t we generalize this perspective?

I honestly believe we should. I think euphemisms protect us to an extent, but one day, we will have to face reality. We hope it will be later rather than sooner, but children will come into contact with death in one way or another. Euphemisms aren’t always useful, and it’s curious to be in the age group I’m in—I’m 33 years old—people around me are starting to have children and struggling with these issues. “How do I explain death to my children? How do I explain death to kids? Should we use a euphemism, take them to the cemetery, take them to a wake, take them to a funeral?”

There’s a project in Portugal called “Filocriatividade.” It’s a philosophy workshop project, and during Cemetery Cultural Week, some workshops specifically focused on these issues of death and mortality to encourage children to discuss these topics. If we give them space, they want to talk; they have questions and doubts.

It seems to me that sometimes euphemisms serve more to protect us, the adults, from having these difficult conversations than to protect the child, who is only afraid of what they know. If we invent euphemisms, we’re not making anything better; it’s better to be clear and transparent. Psychology will have answers regarding the appropriate ages for certain types of explanations, and there we are completely outside my area, but obviously, there will be ages when they’re ready to understand what is permanent and what is not. After all, conversations like: “Dad went to another place.” “But when is he coming back?” The concept of permanence is very complicated at certain ages.

If a child wants to leave a funeral because it’s sad, that’s okay, it’s a child. But funerals and wakes also give us a space where we don’t have to do anything but mourn. This is something we have been losing in our societies. We no longer have the practice, for example, of prolonged mourning, or wearing black to signal to people around us that we are in mourning and that something is happening to us. No; we lose someone, three days later we’re back at work, and it’s expected that life continues as it was before. These little bits of time and space are necessary for us and are useful, but more and more, we are starting to lose them.

We have so little contact that we can even lose someone and never see their body. Nowadays, this is absolutely normal and completely normalized. So, for most people, the first body they will see means nothing. It’s a mummified body in a museum, for example, or a relic of a saint on an altar, or whatever. We go through these experiences without giving them much meaning; seeing a mummy in the British Museum, what does that mean? Nothing. To me, it seems they have great significance

So, how did the idea for this sort of death itinerary come about?

In my mind, this work has existed for a long time; I just hadn’t been able to articulate the various chapters and sections into a coherent narrative. Throughout the book, we visit cemeteries, Chapels of Bones, two different types of saints. So, we go to the religious space, the chapels, the churches, and then we move on to museums, anatomy museums, anthropology museums, natural history, etc. What these spaces have in common is the exhibition of the human body, the dead body, but they exist in a context and are created for entirely different reasons. The body of a saint is not exposed for the same reasons as an ancient Egyptian body in a museum. The motivations are different, and the contexts that bring these bodies to us are different as well. That was what I was missing; how to articulate these things that, in my mind, already seemed unconsciously the same thing, or very similar. What would be the common point between them? I ended up deciding that what they have in common is the exposure of the body. In their different contexts and motivations, it seems relevant to me to discuss these things alongside one another, even though they are distinct.

A museum and a cemetery are not the same thing, but they allow us to have these reflections on the contact we can have with the body, which, today, also begins to be increasingly rare. We no longer dress the bodies of our loved ones at home, we no longer hold wakes at home, we have less and less contact with the corpse, to use the descriptive word. We have so little contact that we can even lose someone and never see their body. Nowadays, this is absolutely normal and completely normalized. So, for most people, the first body they will see means nothing. It’s a mummified body in a museum, for example, or a relic of a saint on an altar, or whatever. We go through these experiences without giving them much meaning; seeing a mummy in the British Museum, what does that mean? Nothing. To me, it seems they have great significance and can help us reflect on several issues, including our own mortality.

This issue of being increasingly separated from death gained gigantic proportions with the pandemic, where rites were increasingly reduced, and often you couldn’t see the bodies. Even after the pandemic, there’s the habit of not being able to touch the deceased, due to preservation techniques, which also conveys that sense of detachment.

That trend started before, all through the 20th century. An American author, Jessica Mitford, wrote a book called “The American Way of Death,” where she talks a lot about the industrialization of death, about death being taken from home and becoming the responsibility of a series of institutions: hospitals, funeral agencies, cemeteries, etc. It seems to me that the pandemic has brought an acceleration point to this trend that was already happening. The fact is that we don’t really have a lot of information; it’s very concrete information about what was before and what was after.

We know that during the pandemic, people were very resentful of the funeral practices they were forced to adopt. Initially, bodies were mandatorily cremated instead of being buried. When they were buried, often the coffin wasn’t opened, which went wrapped in layers and layers of plastic. They buried 10 bodies at a time, in consecutive graves… It created a detachment and an acceleration of these practices. Now, I wonder what will be the medium and long-term effect of this phase of the pandemic and how it changed our relationship with the dead, partly due to public health concerns, which is a lot of what also motivates major changes in how we manage the dead. There was the question of whether a corpse could transmit Covid-19; now we know it can’t, but at the beginning, we didn’t know that. All those concerns and protections in how to touch, move, and handle the corpse we now know were overzealous, but we did the best we could while humanity was in a terrible period.

But, in terms of mourning, I imagine it’s brutal for those who have the awareness that they will never see that person again and didn’t even have that last moment, so to speak.

Yes, and they couldn’t carry out the person’s wishes regarding the disposition of the body. Many people would prefer to be buried or placed in a mausoleum rather than cremated. There are many people who still don’t necessarily understand the logistics of cremation and how it works, but it was a choice that was taken away from families during that period. Obviously, all this has some kind of consequence.

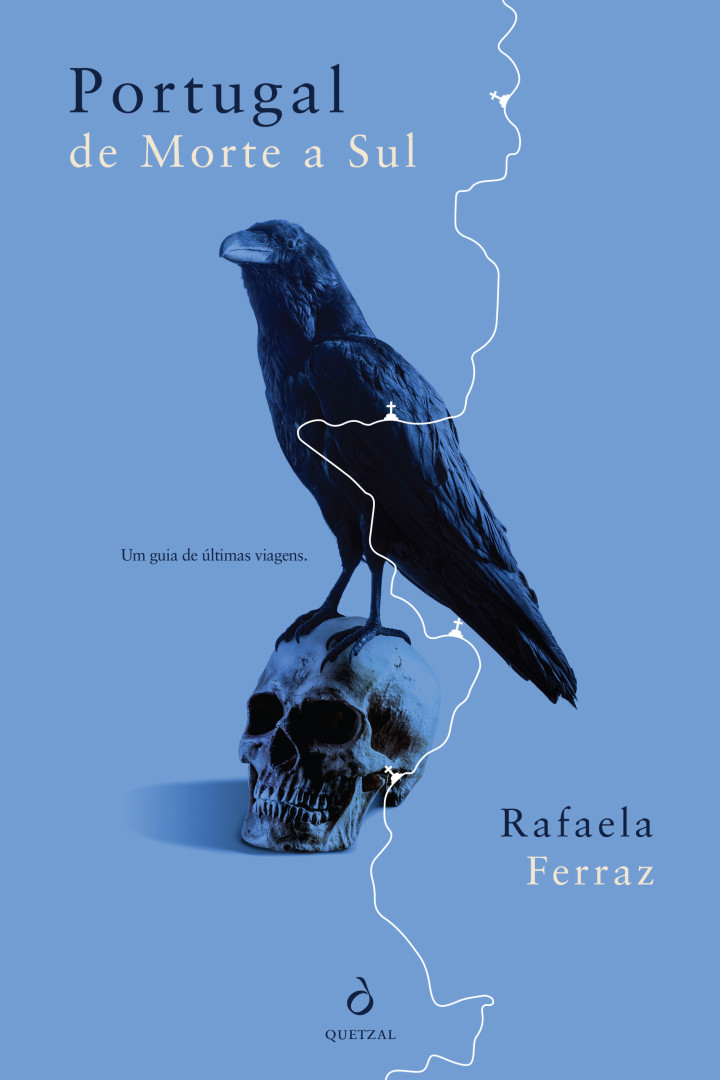

Capa do livro “Portugal de Morte a Sul”, de Rafaela Ferraz© Reprodução/Quetzal Editores

Capa do livro “Portugal de Morte a Sul”, de Rafaela Ferraz© Reprodução/Quetzal Editores

The idea of consent is also heavily present in the book, which invites reflection on the journey bodies make until they reach museums or Chapels of Bones, for example. You mentioned feeling discomfort regarding museums, due to all the related issues. Don’t you feel the same about the Chapels of Bones, considering that these remains have also been transformed into decorative objects, in a way?

My understanding of these two questions has a lot to do with a displacement in time, space, and context. When we talk, for example, about the body of a mummified South American individual, who lived hundreds of years ago and is now displayed in a Portuguese museum, there is a transatlantic spatial displacement. The vast majority of these transatlantic displacements occur in a context of colonialism and power inequalities where, ultimately, Europeans handle and use the cadavers of other cultures as if they were objects and display them. We are the ones exposing them in our museums and cultural institutions as if they were objects. So, there is an objectification of the body, on one hand. It is the body of the other, culturally the other, because it is another person who is inferior to us in this context of colonial thinking, and there is also spatial displacement, where this body is completely disconnected from its land. It’s as simple as that. There is a total displacement geographically, a cultural displacement. These people, who are dead in a museum, are not surrounded by their people or their people’s descendants. There are a series of displacements in time and space that create this discomfort and incoherence for me. There is a term that has been used in academic literature, which is “dissonant heritage.” For me, the museum fits very much into this dissonance issue when there is a body on display.

In a Chapel of Bones, that displacement is much shorter. The Chapel of Bones of Campo Maior, which is one of the examples I mentioned in the book, from what has been understood so far from archaeological work, is built not far from where that community’s burial ground would have been. So, the geographic displacement that happens here is very small; we’re talking meters, but there is no contextual displacement. In the end, these people are buried as Catholics and are elevated to the walls of that chapel as Catholics, to pass a message of Catholic thought. In other words, my understanding is that these people remain integrated into their cultural context and their religious context. That’s my stance; it won’t be everyone’s, even because the Chapels of Bones cause much more discomfort to most people than a mummified body in a museum. We might also wonder why: are we attributing more humanity to the remains we see in a Chapel of Bones versus the remains we see in a museum? Here we enter a series of philosophical questions, but I would say that the key concept has to do with these displacements of context, culture, religion, and, in many cases, geography.

The periodic exhumation and even the transfer of bodies to the National Pantheon also raise these consent issues. You even mentioned the example of Eça de Queiroz.

As someone interested and studying these topics, it was very interesting to see the debate about the relocation or not of Eça de Queiroz, who was in the Baião cemetery and had been in another location before. So, the Pantheon is his third burial location. It was interesting to see over these years all the concepts that arose to defend one position or another: we should honor him because he’s a great man, but it wasn’t what he wanted, but we don’t know what he wanted. And if there’s an indication of what he wanted, do we value or devalue it depending on whether it suits our argument? It was very interesting for me to understand how society can perfectly use and is interested in discussing these concepts. It only arises in this case because we are talking about an almost mythical figure in our literature and culture, and a person who would have many opinions about this topic, at the level of social criticism that could be made from it.

Then, it becomes a comedy sketch, in a way. They make the procession to relocate the body, and horses fall in the middle. They arrive at the Pantheon and put the man in a room where no one else is buried. This has its comedic side, but it raises these questions about what consent for the body is. Or, ultimately, what right do we, being alive, have over the destination of our body? This would be the first bifurcation of the debate: can we decide, or can’t we decide? Today we accept that, in most cases, we can, but there are also degrees of expressed will. Then, there’s the interpretation of the will that a person leaves for the future, and when can this be overridden or erased if it serves a greater purpose. The idea of the Pantheon is somewhat this: does the Pantheon honor Eça de Queiroz’s bones, or do Eça de Queiroz’s bones honor the Pantheon? They are two very different angles of approach. If it’s Eça de Queiroz’s bones that enhance the Pantheon, then they have some power or essence. If the Pantheon honors Eça de Queiroz, then why couldn’t Eça de Queiroz be honored in the Baião cemetery, for example? What does the Pantheon have that’s special to honor these figures that we can’t do in another burial space? This raises a series of questions that also become political and institutional, and that’s not so much the side I’m interested in. But it was very interesting to see society and the media discussing this issue of consent over the body and over the destiny we give to a person’s remains who, in this case, is famous, but could not be.

All the mental burden that usually accompanies the family during or right after a person’s death returns when exhumation is done. And, in most cases, ossuaries are not forever; they are rented for periods of time. So, this is a management that also extends until someone gives up and decides to cremate the bones. In a way, we can say that, for those who don’t have a perpetual grave or a perpetual mausoleum, the management of loved ones’ deaths is a process that extends

Something you mentioned, and that also caught my attention, was the fact that we don’t think about the body after death, that is, the decomposition process. Is it a way to protect oneself in mourning, or is it another barrier we erect in facing mortality?

I would say it is very cultural. Throughout art history—let’s call it Western art or European art—there’s a series of phases in how we contact the body and how the dead body is represented. Today, when we think of death, we think of the so-called dry death. It’s a skeleton with a scythe, sometimes it has a black cloak… A skeleton is not something that bothers us very much; it’s a skeleton, bones, dry, makes a hollow sound. The skeleton doesn’t frighten us, in a way, and I think Halloween is proof of that—we have skeletons all over the place, and it’s no longer an image that shocks us. If we rewind, for example, to the medieval period, death is represented in different stages of decomposition, as something repulsive, more realistic from the point of view of the smells and the sensory experience it provokes. Today, we are very far from being able to think about death that way, and we prefer not to. The question of preserving corpses became common from the 19th century; embalming, thanatopraxy, as it’s called in Portugal. I often call it the beautification of corpses because that’s what it’s for: not for the corpse, but for the living who see the corpse. It sounds like that joke, but there’s a difference between being alive and being dead. Anyone who has ever seen a body sees there’s a difference in coloration, in features… These preservation processes soften the transition a bit between one state and another and thus allow us to perform the funeral rituals without necessarily confronting the reality of the body.

For example, as someone interested in this and who studied Legal Medicine, thus knowing the stages, I’ve already been to funerals or wakes with an open coffin, and sometimes I’d look at the body and think, “Does it look good? Does it look bad? Can we still keep the coffin open? Is it reasonable? Is it not reasonable?” Some people have very intrusive thoughts, sometimes even about themselves: “I don’t want to be buried because I don’t want worms, I don’t know what.” “I don’t want to be cremated because this is going to happen.” We have these images that are diffuse, not very clear, nor very precise. The proof of this is that most people, when they hear about a periodic exhumation, do not know exactly what they are supposed to find. From the moment the body is closed in a coffin, it’s not our problem; it will be someone else’s problem in the future. But, returning to the essence of the question, I would say that yes, it is a way to protect us a bit and mentally preserve the integrity of our body. My body is a watertight entity, let’s say, in the exchanges it makes with the outside. I have barriers; my skin is a barrier, my body is a structure in itself. What happens throughout the decomposition processes is that this structure begins to dissolve; we lose these barriers and limits between the organs and layers. This is very impactful because we are something complete and we cease to be that as we decompose. It’s an absolutely natural process, and we understand it is natural because sometimes people say they would like to return to nature, to be buried with a tree, etc. There, we can imagine the decomposition issue as something positive: it is something that returns us, ultimately, as organic matter, to nature. But in most cases, I think we prefer not to think about it and not expose ourselves to such thoughts.

It may also be because we don’t want to think of our relatives and loved ones in that way. I recently talked with writer Valter Hugo Mãe about the book “Educação da tristeza,” where he recounts the episode of his father’s exhumation ten years after his death. However, the body wasn’t completely decomposed. The portrait he paints is absolutely horrible because he wasn’t expecting to see his father in that state.

I’ve never experienced witnessing an exhumation, either of a relative or a stranger. What I’ve heard and what I’m told, even from people who work in the area or work in cemeteries, is that a bit of everything happens. Some people are deeply shocked, while others feel they already had their mourning almost resolved and start anew because they had a new contact with death, but in a different version. There are also people who have an absolutely natural reaction. I think I read this in a doctoral thesis, but two typical frequenters of the Portuguese cemetery, who spend a lot of time taking care of their loved ones’ plots, witness the exhumation of someone they knew and comment that they can still perfectly recognize the person, with a naturalness that is bizarre. Or it’s so far from how many of us think about death that it seems impossible that someone could relate to death this way. Yet, there it is. These people spend a lot of time in the cemetery, so they must be more than trained for this.

The experience I am told is that periodic exhumations confront us with death in a different way. There are no good visual contacts; either we find bones, or we find something worse. As I said earlier, dry death doesn’t disturb us much—bones are bones—but the intermediate stages are a bit more uncomfortable. Then, there’s the whole logistic issue that needs to be managed again. If the body isn’t exhumed, it’s covered again and will be exhumed again in two years, in most cemeteries. If it’s exhumed, then you need to choose what to do with the bones: if they’re cremated or incinerated if they’re placed in a little box in an ossuary in the cemetery. All that mental burden that usually accompanies the family during or right after a person’s death returns when exhumation is done. And, in most cases, ossuaries are not forever; they are rented for periods of time. So, this is a management that also extends until someone gives up and decides to cremate the bones. In a way, we can say that, for those who don’t have a perpetual grave or a perpetual mausoleum, the management of loved ones’ deaths is a process that extends and is constantly being renewed and reconsidered as the bones have to go through these different steps. If this is a more violent or less violent process, I think it will depend a bit on the individual stance and relationship with that death and with that specific person.

Anyone who has ever entered a very small rural cemetery will have experienced seeing only one tomb. So, who might that tomb belong to? Understanding who that family is will likely reveal a lot about the history of that place and community. We have epitaphs that are often descriptive of who these people were; we have graves decorated with professional or religious symbols, which indicate something about the identity of these people. All of this contributes to local history

Then, there is a space for the dead and a space for the living; I think that’s clear. But isn’t the cemetery, traditionally associated with death, also a space full of life?

Yes, absolutely. It’s a very cultural question, if we think about what we’re going to do at the cemetery and what is done in the cemetery. In Portugal, the cemeteries we have are of romantic origin. They are built during the Romantic period, in the 19th century, following a series of guidelines and ways of thinking that are very typical of that time. On one hand, the idea that we need to separate the dead from the living because they are a public health risk—as it was said, the emanations from the corpses are toxic and will cause us diseases, so cemeteries are built apart from the center of the community. We don’t have that perception today because cities have since expanded, but the vast majority of the large cemeteries, when they were built, were on the outskirts. The cemetery is built apart from the city of the living and has a series of features—walls, gates, cypresses, trees—that serve to create barriers and limit that space. That is the space of the dead, and this is the space of the living.

However, we are in full Romanticism, which is a period where there is an exaggeration of emotions and the emotional load of practically everything. Death, obviously, is a phenomenon with a huge emotional burden exacerbated in Romanticism, enveloped in a series of euphemisms. We start thinking about these things, these ideas of eternal longing and eternal sleep, that the person has departed and is in a better place, and we will remember them at their best. This brings us all that very typical funerary architecture of this period, which greatly glorifies the deceased, with those very laudatory epitaphs. But all these constructions are for the living, not the dead. The dead are not seeing the epitaphs, they are not seeing the sculptures. We have these two lines of thought, which end up resulting in the cemeteries we have today: although they have many characteristics that separate us from the dead—the dead are inside the coffin, inside a tomb, inside a grave—they also have many features that attract the living, such as art quality and epitaphs. Depending on the cemeteries, we have very wide avenues, which are clearly made for us to wander around, to walk and enjoy that space. In Portugal, it’s not as clear as in some other European countries, where the cemetery is more wooded and more gardened. It is a space for socializing, for public enjoyment, more than necessarily our cemeteries which, for the reasons I mentioned, are not integrated into the urban space and are always fenced.

Moving to the 21st century, what we see is that, indeed, there is a lot of life in cemeteries. We just passed All Souls’ Day, and anyone who visits a cemetery on November 1st or 2nd, in the weeks immediately before and after, notices that there is no lack of life in cemeteries; there is no lack of people taking care of graves, decorating plots, leaving candles. Sometimes, candles are left on graves that aren’t theirs, just because they feel a moral impulse. We see many community phenomena. If there is a child’s grave, it is very common for several people to decorate and take care of that grave, even if it has nothing to do with their family. If the flowerpot is tipped over, someone straightens it. There are a series of small community experiences happening in the cemetery demonstrating plenty of life. Walking in the cemetery, I see brooms behind graves, sponges, microfiber cloths, and cleaning products. It seems to me that it’s an extension of the domestic space. A series of tasks that we do in the domestic space and that women usually assume are also taken to the cemeterial space: caring for flowers, making arrangements, cleaning, decorating. There are graves with rosaries, beads, and flowers. In essence, this beautification done in the domestic space is also done in the cemeterial space. I believe it’s for a very sentimental and religious reason, but it benefits us all when we walk through such a space and see these signs of life and community.

I think there is no arguing that there is life in cemeteries because we see it every time we’re there. We could take this argument much further; we could say that many cemeteries have cat colonies maintained by municipalities. It’s yet another layer of life that exists in the cemetery. Many cemeteries, being relatively gardened spaces, manage to have some concentrations of biodiversity, and even plants that are not common in other parts of the city. There are many layers of life in the cemetery that we cannot see as easily in other spaces of the city.

Yes, even the stories themselves, or snippets of the deceased’s stories, are present in the cemetery.

Yes, anyone interested in the history of their locality, no matter how big or small, will find many clues in the cemetery. Anyone who has ever entered a very small rural cemetery will have experienced seeing only one tomb. So, who might that tomb belong to? Understanding who that family is will likely reveal a lot about the history of that place and community. We have epitaphs that are often descriptive of who these people were; we have graves decorated with professional or religious symbols, which indicate something about the identity of these people. All of this contributes to local history. The bigger the place and the cemetery, the more variety of stories we can get.

It seems to me that, when it’s the dead of others, from a historical perspective, there is an enormous objectification and depersonalization of what these bodies are. We always return to the example of the museum; seeing corpses in the museum has become completely normalized. If we go to the British Museum and there isn’t a mummy, we are even disappointed, right? It’s what we’re expecting to see when we enter an exhibition about ancient Egypt. And yet, that mummy – mummy object – is a person

Here in Porto, for example, I always think about the story of the Teatro Baquet tragedy, where many people died. I didn’t know the story until I reached the Agramonte cemetery and saw the monument to the fire victims. The monument is decorated with debris taken from the theatre, including iron pieces, but not just that. Essentially, we have in that space, perpetually preserved, a piece of the city’s history that is not visible if we go to the location where the theater was, which is now a hotel. If we go to that location, we have no idea what was there and the catastrophe that occurred there. That history was recorded in the cemetery, not in the city’s space.

Are we more empathetic towards the dead, considering the care we take with graves, for example?

That’s a good question. With ours, perhaps. It’s said that when a person dies, only good things are said about them; we don’t speak ill of the dead. We are undoubtedly laudatory in some aspects, but not all. There are many cases where someone dies, and people say, “it was about time.” It might be argued that death polishes some rough edges in our interaction with the person because it interrupts future interaction. Therefore, only our version of everything that happens from here on exists. I don’t know if that translates into more empathy, but it’s very easy to forgive someone I will never deal with again. I think this challenges the thesis of the book a bit because it seems to depend a lot on the dead. With ours, perhaps; those close to us, our family, our friends.

It’s possible that death truly improves or alleviates some relationships with people who were close to us. However, when they are the dead of others, from a historical perspective, there is an enormous objectification and depersonalization of what these bodies are. We always return to the example of the museum; seeing corpses in the museum has become completely normalized. If we go to the British Museum and there isn’t a mummy, we are even disappointed, right? It’s what we’re expecting to see when we enter an exhibition about ancient Egypt. And yet, that mummy—mummy object—is a person who had a life, had relationships, knew other people, had contexts, and lived very far from here, in most cases. It seems to me that the way we treat our dead and the dead of others is very distinct. And we continue to see this with media coverage of some catastrophes. A Portuguese dead is worth more than 500 Palestinian dead, for instance. There is such great depersonalization and distancing that death is clearly not the same for everyone.

Despite the physical and mental barriers society seeks to create between the living and the dead, the fact is that cemeteries are a mirror of social asymmetries, and even in death, we aren’t rid of these compartments.

Not at all. And it’s a reasoning that’s contemporary to the creation of the cemetery; Fialho de Almeida writes about this, Ricardo Jorge writes about this. The idea of identifying hierarchies in the cemetery isn’t new. All cemeteries have slightly different regulations, although they follow a standard national model, and there are categories of cemetery space. So, at the top of the hierarchy, we have the perpetual mausoleum, which is the family mansion, the family estate in the space of the dead. We have the perpetual grave, which can be individual but is forever. And then, we move on to the temporary grave, which is, I would say, the standard in large urban cemeteries today. We can see this scale in large cemeteries in Lisbon, for example, which have a great extent of temporary burial. We have drawers that, depending on the cemeteries, can be perpetual or temporary; it’s a complex war to explain because the typologies vary greatly from cemetery to cemetery. And until a certain period, we had the common grave, which was the base of this pyramid. The common grave is prohibited by the 1835 funeral legislation but persists until the early 20th century, regardless of being illegal or no longer part of the cemetery’s legal order. It remains active in Lisbon, for example, until 1941. The common grave is not a medieval phenomenon.

These asymmetries reflect, after all, a perpetuation in time and space. In space because, if I build a mausoleum in 1840 and my family will continue to use it, 100 or 200 years later, it will still be there. So, I can perpetuate my family and ensure a burial space for all my family members, which was incredibly important when cemeteries started being planned. There’s also a perpetuation in time because what I engrave on these graves, what I leave written about myself and my family, is the word that will endure until the moment no one knows me anymore. Essentially, all the people who knew me have already died, but my name continues perpetuated in the cemetery space, which is a public space. I think we have to consider the cemetery as a public space. I can’t erect a statue to myself in a roundabout, but I can build it in the cemetery if I have the funds to buy the perpetual space.

People don’t necessarily want to photograph themselves with a mummified body, or there isn’t so much that instinct; although there are photographs and cases of tourists in museums who have overstepped a little. In the Chapels of Bones, we see people juxtaposing or overlapping themselves to the chapel space and comparing themselves. So, I stand in front of a wall full of skulls, and I’m there in the middle. What am I saying with this? What I interpret is that we can feel the parallelism

When we move to temporary burial, this perpetuation doesn’t exist either in space or time. Several names are literally erased; they exist for five or ten years, but when that grave is lifted, or when that body is exhumed, any inscription there disappears. So, the material record of that person’s passage through that space completely disappears. The common grave is the ultimate expression of this, where there isn’t even a material record of those people’s passage there, to the point that today we don’t even know the location of enormous structures like a common grave in many large urban cemeteries. There are renovations, reconstructions, plots are built on top…

These asymmetries still exist today. If we look at municipal fees for many cemeteries, we clearly understand that the price of a perpetual grave is absolutely prohibitive in a country with our standard of living. Therefore, we resort to other options: temporary burial, cremation. I don’t want to argue that the cost issue is the only reason someone opts for cremation because it’s not, but there is a very high monetary barrier that prevents access to eternity. From the beginning of cemetery history, it is something limited only to a few, and it continues to be.

Faced with a Chapel of Bones, a mummy, or an incorrupt saint, few people can resist taking photographs. How do you explain this? Is it that lack of empathy for the other?

The issue of photography made me think a lot. In the book, there comes a certain point where there are no more photographs, or there start to be fewer photographs. We don’t have photographs, for instance, of the bodies displayed in museums. It was a decision I made, and it is related to these issues of objectification and empathizing or not with these bodies. It seemed to me that, however much we might take a photo that tries to humanize these people, the exhibition may already be contributing to this phenomenon. It was a personal decision and reflection.

Photography can come from many places. I mention the example of photographs in the Chapels of Bones because I always find it amusing that people photograph the chapel but also photograph themselves in the chapel. People don’t necessarily want to photograph themselves with a mummified body, or there isn’t so much that instinct; although there are photographs and cases of tourists in museums who have overstepped a little. In the Chapels of Bones, we see people juxtaposing or overlapping themselves to the chapel space and comparing themselves. So, I stand in front of a wall full of skulls, and I’m there in the middle. What am I saying with this? What I interpret is that we can feel the parallelism that the Chapel of Bones inspires in us: these people are like me, I am like them. Essentially, the intention of building these spaces is to make us reflect on mortality, as that famous phrase says. “We bones that are here, await yours.” This flattens some of the hierarchies; it makes us think that, just as these bodies became skeletons, one day, I will too. They were once like me, and one day, I will be like them. There’s the idea of comparing my scale to the scale of the skulls on the wall, observing how many teeth they have…

I’ve never seen anyone take a selfie with the body of Santa Maria Adelaide, for instance. The vast majority of people I see in the chapel aren’t even taking pictures; they are interacting with the saint, on the level of their faith and in the context of their faith. They talk, pray, kiss the hand, and put it on the glass, for instance. There are a series of interactions already outside this context of a tourist visit. In the museum, we see a bit of everything. Some want to photograph everything; some prefer not to photograph anything. Some are sensitive to a more sober environment experienced in some museums when a human body is displayed in a room. But we also see a lot of curiosity. When there’s a mummified body on display, it’s very common for people to look over and under, to see what the sarcophagus looks like, what the nails are like…

There are many ways to relate to these bodies, and I would say the question of photography also inserts itself here. I can’t standardize the motivations that may lead us to take photos—except for the Chapels of Bones, which seem to me a phenomenon completely apart from the rest, where we want to become part of that bony crowd, so to speak. In other places, I leave it to the discretion of those who take them.

You confessed that you don’t think much about death, but you think a lot about the dead. Isn’t thinking about the dead inadvertently thinking about death?

Without a doubt. I make the joke that I don’t think about death with a capital ‘D,’ because there are a series of questions I accept might not be knowable. What comes after death? I don’t know. I’m not a religious person; I don’t worry about that; I don’t occupy myself with that thought. What comes, will come. If it’s nothing, it’s nothing. If it’s something, we’ll manage when we get there. I’m sometimes asked, “What do you think of near-death experiences? Do they really see a tunnel?” I don’t know; it’s outside my circle of interest. That’s a bit of what I mean when I say I don’t think much about death. Death is a very big thing; philosophically and religiously, and even from an artistic point of view, it occupies us since we exist as humanity. I feel that if I only thought about death with a capital ‘D,’ I probably wouldn’t think about anything else, and my life would be highly compromised. How can it not be, knowing we are heading there? When I say I think a lot about the dead, I refer to these questions we have been discussing: how do we interact with the body, how do we interact with a person after they have passed to the other side, whatever might be there. How does a city manage the dead, specifically? These are the questions that interest me a little more.

What seems to me to be more or less in place is that if it exists, if it has been preserved, the head of Diogo Alves is most likely one of those skulls, and not the head we’ve seen many times in photos, inside a jar. After all, it wouldn’t make sense; if I wanted to feel a skull, why would the head be intact? It seems to me that it is still a question open for someone to academically reveal one of these days

You said your grandmother and death were on familiar terms. Shouldn’t we generally promote and adopt that perspective?

Yes, I open the book with that expression from my grandmother because it was an expression she used in the first person: “Oh, dear, you wouldn’t believe what happened to me today. I saw death in front of my eyes.” And then, there was always a story of an accident she had, where she thought she was going to die. This was practically daily; every day, she had a near-death experience, as we said earlier. I’m exaggerating, of course, but death was very present in the way she thought about day-to-day life. She had this idea very much present, that death could happen at any time. If someone was in the hospital for a long time, we had to think about going to the wake. The person hadn’t died yet but was already thinking about the wake. Should we encourage this? Maybe not. I think when we think too much about this shroud of death, or when we allow this shroud to fall upon everything we do in our lives, it can compromise us a bit, and we might enter a logic of extreme anxiety about death. It’s even an issue that many people work on psychologically. I think we should talk about it, make it natural, be able to talk about death as we are doing here, in its different aspects and manifestations. If we can create a barrier that prevents death from permeating all our thoughts and actions, it could be beneficial. Psychology will have better answers for this. For example, who hasn’t heard those recommendations that we must wear good socks because we might end up in the hospital, and then we’re in the hospital with a sock with a hole in it. Now, let’s try to translate this into a thought relative to death. What if I die today? I didn’t leave my house tidy. I was supposed to do something and didn’t. Where are the bank papers? There is a level of awareness that can be a bit debilitating and disturbing for day-to-day life.

And what is, after all, the story of Diogo Alves? Preserved head or skull?

Diogo Alves was a man who lived in Lisbon in the mid-19th century. He was Galician and emigrated to Lisbon, like many other Galicians in that period. He did a series of physical jobs and became a legend, as the “serial killer of the Águas Livres Aqueduct”. The story is that he would station himself in the aqueduct, which was used as a footpath, rob people passing by, and push them. He is said to have killed around 70 people this way. This is the legend of Diogo Alves. What we know from the historical record and the legal record is that at a certain point in his life, Diogo Alves forms a criminal gang, which is involved in a series of robberies. The only robbery for which they are condemned is at a doctor’s house in Lisbon, on Rua das Flores, where they kill four people. There is also a fifth death associated with this crime. So, Diogo Alves and his accomplices are sentenced to death for having killed five people.

How do these two things end up coming together and forming a legend? It’s a question that still eludes me a bit. After being sentenced to death, Diogo Alves and his accomplices are hanged, which was the standard execution method at the time. We know that during this period, there are doctors in Lisbon, at the medical-surgical school, who want to study or plan to study the skulls of those condemned to death. We are in an era where we still can’t properly speak of Anthropology or Criminology, but there is already an interest in analyzing specifically the skull, to try to assess a person’s temperament. What was believed is that if we felt the skull’s bumps, we could see which side was more developed and if associated with empathy or whatever. They were very interested in studying criminals’ skulls, to compare them with those of so-called normals, and see if crime was something inscribed in the body, if it was innate. It is said that Diogo Alves’s head was preserved in a jar of formaldehyde and that this is the head at the Anatomy Institute in Lisbon. What we see in the record and inventories in the museum is not this. There’s a head preserved in a jar, which I couldn’t identify who it belongs to.

Diogo Alves’s head, in the inventories, is a bony skull, part of a set of six skulls. This set includes the skull of Francisco Matos Lobo, a murderer also sentenced to death one or two years later, in the 1840s. Ambrósio da Costa’s skull, also a murderer sentenced in this period, two of Diogo Alves’s accomplices, and a sixth person not identified in the inventory. If we look at the Anatomy Institute Museum’s inventories, for a certain period, these six skulls are identified as belonging to hanged criminals. The expression used at the time was “killed by suspension,” a curious euphemism.

Henriqueta manages to have Teresa buried in a perpetual mausoleum; the mausoleum is still there, and as far as we know, Teresa de Jesus is still within that mausoleum. But when Henriqueta dies, she is buried in a temporary grave. Currently, we don’t know where she is. I was recently at a lecture on the subject and realized, from the parallel conversation that was happening, that we don’t exactly know where Henriqueta’s body is. So, there’s all this effort that a woman makes to perpetuate another woman she loved or liked, but she herself has no one do this for her

What seems to me to be more or less in place is that if it exists, if it has been preserved, the head of Diogo Alves is most likely one of those skulls, and not the head we’ve seen many times in photos, inside a jar. After all, it wouldn’t make sense; if I wanted to feel a skull, why would the head be intact? It seems to me that it is still a question open for someone to academically reveal one of these days. I hope to read that work soon because it is a question that haunts me, and I would also like to know the answer.

Of all the stories you’ve come across, is there any you would like to highlight or that has particularly caught your interest?

I always have to choose between two. Let’s go for Henriqueta’s story, the famous Henriqueta here in Porto. Henriqueta Emília da Conceição built a mausoleum in the Prado do Repouso cemetery. The mausoleum is identified on maps as “monument built by Henriqueta Emília da Conceição.” Who is buried there is not Henriqueta Emília da Conceição. This is already distinct because most graves are identified based on who is there, not on who commissioned or owns it. A good example is Camilo Castelo Branco’s mausoleum in Lapa. People know that Camilo Castelo Branco is there, not who owns the mausoleum; that’s not relevant. Here it’s the opposite. We know it was commissioned by Henriqueta Emília da Conceição; we don’t know who is there. That person is not identified on the monument itself or the informational plaque, which was later placed by the Porto municipality.

Who is there is Teresa de Jesus. These two women would be, initially—as they were referred to at the time—prostitutes. Today we would probably use the expression “sex workers.” We don’t know exactly how they met; we don’t know what the nature of their relationship was. There’s a lot of legend involved here; they could have been friends or lovers. It happens that Teresa de Jesus dies relatively young and is buried in a temporary grave in a particular section of the Prado do Repouso cemetery. Even the exact section where she is buried is under debate. A year later, Henriqueta requests the relocation of Teresa de Jesus’s body to a perpetual mausoleum that she had purchased. That is what she decides to do for her friend/lover/whatever the relationship was. A year later, the relocation is done, and legend and historical record agree that at that moment, Henriqueta takes Teresa’s skull from the body to preserve it at home. Later, a skull is indeed discovered at Henriqueta’s home.

There’s a series of fascinating issues here. On one side, this devotion we see of one person towards another, showing how important it was to ensure a dignified burial, besides the importance given to the perpetuation of memory in 19th-century cemeteries, to the point of one woman deciding to do this for another woman, without necessarily knowing the reasons. This devotion is fascinating. Henriqueta’s own relationship with Teresa’s body, to the point of separating the skull and keeping it at home in a small altar, is also very intriguing when viewed in light of other stories in the book. For instance, the relics of saints. Body parts were separated, never intending disrespect but intending to venerate or honor. It’s different from what we see in the Anatomy Museum, where parts are also separated but to classify or identify a pathology.

Henriqueta manages to have Teresa buried in a perpetual mausoleum; the mausoleum is still there, and as far as we know, Teresa de Jesus is still within that mausoleum. But when Henriqueta dies, she is buried in a temporary grave. Currently, we don’t know where she is. I was recently at a lecture on the subject and realized, from the parallel conversation that was happening, that we don’t exactly know where Henriqueta’s body is. So, there’s all this effort that a woman makes to perpetuate another woman she loved or liked, but she herself has no one do this for her. This brings us back to that reflection on the will or right we have over our own body and how much it depends on the people around us. We can have all the desires in the world, but if we don’t have anyone to exercise them or make them exercised for us, that desire is worth very little. It’s a rich story, and I like it a lot.

It’s clearly relevant for the city of Porto somehow because that mausoleum is always decorated with candles and flowers. Now, on November 1st, it had candles everywhere. The mausoleum has a statue of Saint Francis, whose arm is slightly bent. So, there are always flowers placed on the statue’s arm, which we don’t exactly know who leaves. One day I’ll have to join the group and leave something there. It’s a story of devotion that perpetuates over time, even though one of the story’s participants hasn’t perpetuated at all.