The book “Algoritmocracia”, addressing how artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming democracies, was penned in response to current political landscapes, the author explains.

“Politics has become significantly more polarized, radicalized, binary, and manichean, where the space for moderation is shrinking and populists are gaining substantial electoral power, if not winning elections outright,” he remarks.

Within this framework, questions arose about why this is occurring across Europe, including within his own political realm, spanning right and center-right factions. The conclusion drawn is that the algorithmic ecosystem greatly informs this observation: “the book emerges from this reflection.”

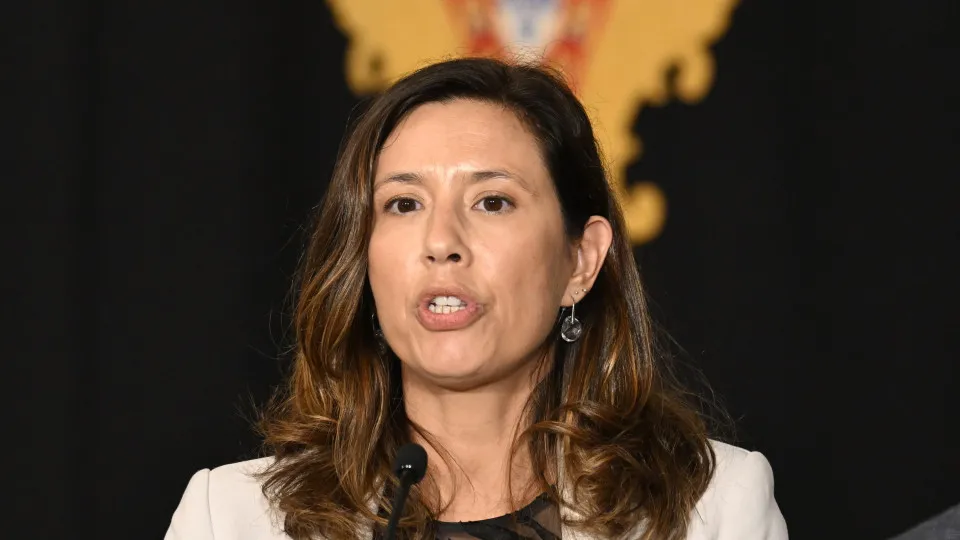

“It’s crucial to recognize that we’re handling something novel and to reflect on it,” as “the gateway to the world,” the process of forming opinions, has become “more passive than active,” says Adolfo Mesquita Nunes.

Previously, “we bought newspapers, watched newscasts, actively sought information. Today, it arrives daily in various forms, even in non-informative content,” through videos, parodies, or articles, among other mediums, he explains.

The delivery of such articles and videos is not random: “it’s programmed via algorithms that determine which videos we watch, which ones we don’t, in what sequence, and at which times, and this is a critical starting point for this reflection,” warns the lawyer.

Mesquita Nunes notes, “It’s understanding that there exists some structure unknown to us, which we never requested, whose control is unclear, which we never defined nor personalized, yet dictates exactly the content we see and read, and when.”

“This means our opinion-forming process is mediated not by newspapers, television, teachers, or friends, but by algorithms,” he points out.

Earlier, “we could critique teachers, journalists, choose another newspaper, or counter editorial choices,” but now such opportunities no longer exist, he affirms.

“Should you wish to counter the algorithm, it’s impossible, to grasp its workings is out of reach, or to understand its content recommendations is unattainable,” he cautions.

For instance, “if we were told the government chose daily the news we read or didn’t read, the videos we watched or didn’t, and controlled the information reaching our phones, we would label it autocratic,” he says.

“Well, that’s precisely what’s happening: it’s not the government, but the algorithms,” Adolfo Mesquita Nunes concludes.

“There is an algorithmic structure crucial to what we see, thereby influencing our opinion formation process,” he states, explaining that studies indicate human nature is particularly sensitive to certain content types.

This process slowly shapes and guides opinions, steering people towards specific ideas. Crucially, Mesquita Nunes emphasizes, “there isn’t an active force wanting Adolfo to think A or António to think B.”

Algorithms aim for attention, seeking to maximize online duration for revenue rather than persuasion.

Furthermore, these algorithms are “devised by scientists well-versed in brain functions,” with humans being “especially drawn to content that shocks, mystifies, frightens, outrages, or incites resentment,” he elaborates.

“This is not to negate existing emotions, biases, perceptions within us, independent of algorithms,” yet undeniably, the algorithms exacerbate these, sometimes disproportionally, asserts the former Secretary of State.